ChatGPT and Watermarking

In November 30, 2022, OpenAI released ChatGPT, and (at least in my opinion) it changed the world a lot, because of its standout performance. It can do a lot of things, including writing a code, poem, movie script, solve some math problems, and searching. We can literally (try) to ask any questions to ChatGPT, and it give us answers which are likely to be true. Of course it gives wrong answer sometime, and actually quite often when we ask hard questions (like research-level mathematics). But it works well for a lot of tasks - see here for example prompts that you can try.

I also tried and enjoyed it a lot, and an obvious question arose in my mind - why it works well? Why ChatGPT is better than the vanilla GPT, which was published in 2018? I’m going to give an answer based on the paper and OpenAI’s blog post.

Also, I found a recent paper uploaded on arXiv on watermarking large language models. Such a watermarking is somewhat essential due to the bad use of ChatGPT or ChatGPT-like models - e.g. using it for writing homeworks or generating fake news. This is another thing that I’m going to explain here.

ChatGPT vs GPT - what’s the differences?

Obviously, to understand how ChatGPT works, we need to understand how GPT works first. GPT is an abbreviation of Generative Pretrained Transformer. If you never heard about these concepts, then here are some brief explanations for you. You can find a ton of great resources that explain way better than me on Google or YouTube, and I’d recommend those for you who want to know more in detail.

Pre-training and fine-tuning

At some point, pre-training and fine-tuning paradigm become a de facto method for obtaining a deep learning model with high performance. It is also called transfer learning (some people distinguish these two, but in this post I’ll consider them as a same thing), and let’s explain it with the image classification problem.

In general, we need a lot of data to successfully train a deep learning model and get a model with high performance. However, in the real world, it is very often to have only a small amount of (labeled) data. For example, assume that we want to classify medical images labeled with diseases. We certainly may not have a lot of such images, and it is even hard to get such images due to privacy concerns. To address this issue, we first train a model (neural network, e.g. a ResNet) on a large dataset such as ImageNet (which contains 1 million images). This is the pre-training step. Then, our belief is that, if the model is trained well on ImageNet, it may learn how to classify images well, and such knowledge might be able to be transferred to other images. For this, we take off the classification layer of the pre-trained model and replace it with a new classification layer for our own classification (medical image classification). Then, we fine-tune the replaced layer, fixing the remaining parameters of the pre-trained model. In other words, we use the pre-trained model as a feature extractor (encoding an image into meaningful vectors) and use the extracted features for classification. Surprisingly, it is known that models obtained in this way perform significantly better than models trained from scratch (i.e. trained only with the given medical images).

Transformer

Transformer is a neural network architecture that is commonly used for tasks such as natural language processing. It differs from previous architectures like recurrent neural networks (RNNs) in the way they process sequences of input. RNNs process sequences by recursively applying the same set of weights to the current input and the previous hidden state, while the transformer uses self-attention mechanisms to weigh the importance of different parts of the input sequence when making predictions. Additionally, transformers can process the entire input sequence in parallel, which makes them more efficient in terms of training and inference time. After the birth of Vision Transformer, they are even used in computer vision tasks like image classification.

Generative Pretrained Transformer, aka GPT

So, what is GPT? As it says, it is a transformer-based model which is pre-trained in a certain generative way. In fact, it is trained to predict the next word (to be precise, it has to be the next token. However, I’ll not distinguish word an token in this post for simplicity). Here generative means the following: it is pre-trained to predict the next word based on a given sequence of previous words. For example, if we have a sentence like “I like mathematics. My hobby is to solve math problems.”, then the model is trained to

- predict “I” from an empty sentence,

- predict “like” from “I”,

- predict “mathematics” from “I like”,

- …

- predict “problems” from “I like mathematics. My hobby is to solve math”.

Such a generative pre-training is a type of language modeling, and its goal is to learn a distribution of natural language sentences in a generative way. Ther are other types of language models like Word2Vec, ELMo, and BERT. These learn a distribution of natural language sentences in their own ways, and result in nice word / sentence embedders (represent a word / sentence as a vector). Such embeddings can be used to solve downstream tasks like sentimental analysis or machine translation, and show great performance improvement (especially transformer-based models like GPT and BERT showed huge improvement).

However, for text generation, GPT-like models might be the best choice for generating human-like sentences in a sequential way, simply because of how it is modeled. With large GPTs (e.g. GPT-3 with 175B parameters trained on huge text corpus), feeding certain prompts into it generates some useful and human-like texts that we want. For example, you can translate an English sentence into French by using a prompt something like Translate this sentence into French: I like cats., and GPT-3 will generate a translated sentence similar to J’aime les chats.

InstructGPT, the backbone of ChatGPT

I believe you understand what GPT is. Let’s move on to InstructGPT, the backbone of ChatGPT. You may also read the OpenAI’s blog post on it.

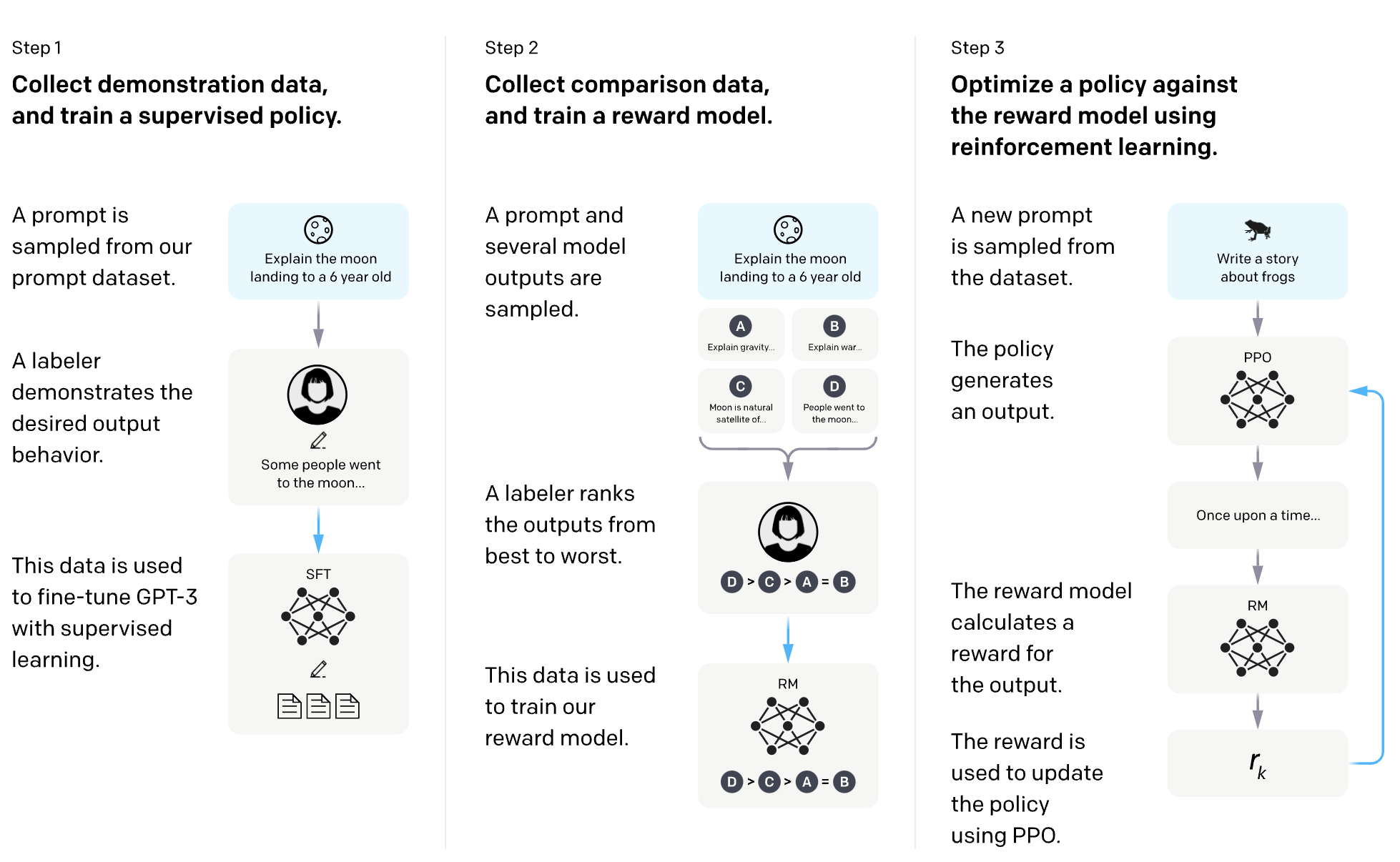

GPT-3 works well, but not perfectly. It produces wrong/harmful/hate sentences sometimes, and we need to reduce such bad generations (it is impossible to eliminate them perfectly). Toward this, they combined GPT-3 with Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF), which use a reward model trained with human preferences. They first fine-tune GPT-3 using human-written demonstrations on prompts. Then collect human-labeled comparisons two model outputs on a larger set of API prompts, and use the labels to train a reward model (RM) that predicts human’s preference. Lastly, they fine-tune the GPT-3 again with RM using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), which is a reinforcement learning algorithm also designed by OpenAI. For the readers who don’t know the concept of reinforcement learning, training GPT-3 with PPO make it to generate sentences with higher and higher rewards.

By combining the existing GPT-3 with RLHF, they could obtain much better GPT with less harmful outputs (see the above blog post on InstructGPT for the details of the metrics they use for the evalutation). This is how ChatGPT really works, especially why it is better than GPT-3.

Recently, there was a concern about human labeling procedure for ChatGPT - see this NYT article.

Watermarking ChatGPT

So ChatGPT works well, actually very well. Hence it is essential to detect whether a given sentence is generated by ChatGPT or other (large) language models or not, since there are so many misuses of it like doing essays or making false news. But it looks like a really difficult problem, to decide whether a human-like sentence is really written by a human or a human-level AI (note that I don’t think ChatGPT is perfect at all - just it works very well on certain tasks).

In this paper, the authors suggest a way to watermark large language models. In other words, they suggested an algorithm to embed hidden messages in a generated text that is not visible to humans but algorithmically detectable from a short span of words. The main idea is also well-explained in this author’s twitter thread, but I’d try to reproduce and add a little bit more details based on the paper.

Watermarking process can be described as following. When (Chat)GPT generates words one by one, instead of chosing a word from whole possible set of vocabularies, it first randomly divide the vocabularies into two parts - a whitelist and a blacklist - and only choose a word from the whitelist. Here we need to fix a random seed for detection stage, and the authors suggest to use hash of the last token generated. Then we can detect watermark without any access to the actual model as follows: we can check whether each word in a sentence is in the corresponding whitelist (that is determined by the previous word’s hash), and simply observe how many words in the sentence are in the whitelists. If most of the words are from the corresponding whitelists, then the sentence is highly likely to be generated by the (Chat)GPT. If the sentence has $T$ words in it, then the probability that a human generate a sentence without violating the above blacklist rule is only $1/2^T$, which is highly unlikely even when $T$ is pretty small. More precisely, we set a null hypothesis as follows:

\[H_0: \text{The text sequence is generated with} \\ \text{no knowledge of the blacklist rule.}\]Then the $z$-statistic for the corresponding test is

\[z = \frac{2(|s|_w - T/2)}{\sqrt{T}}\]and use this to reject the null hypothesis $H_0$ and detect watermark if $z$ is above a certain threshold, e.g. when $z > 4$. Following this, it is also hard to remove watermark - you need to replace a lot of (whitelist) words in the generated text.

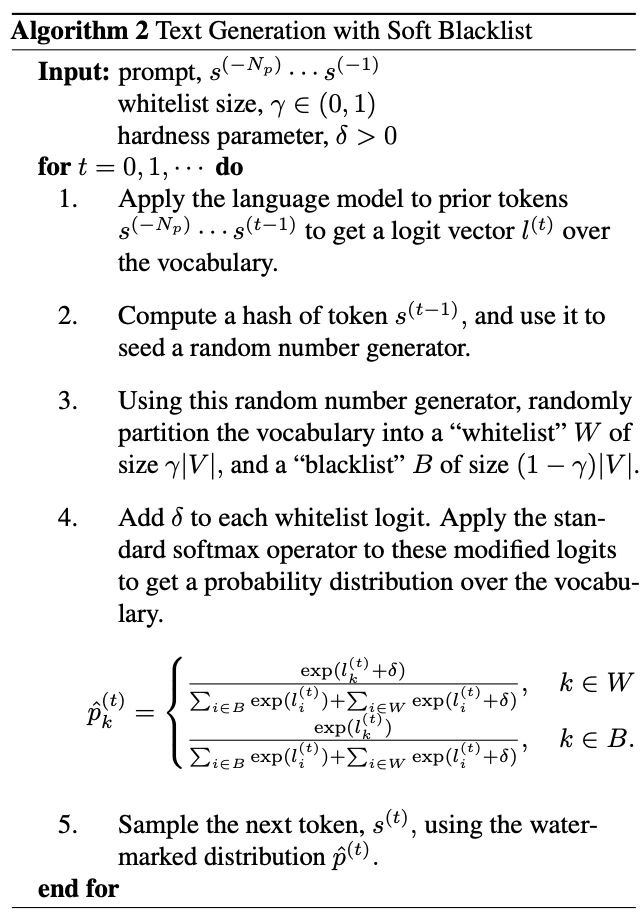

However, there is one obvious issue with such a hard blacklist approach - it can degrade the performance of the model (i.e. poor generation quality). For example, we all agree that there’s one obvious choice for the upcoming words of the sentence “SpongeBob Square”, and the above random split might put “Pants” in the blacklist. To avoid this, we need a sophisticated watermarking process. The soft blacklist algorithm is based on the choice of a whitelist size $\gamma \in (0, 1)$ and a hardness parameter $\delta > 0$. When (Chat)GPT generates a sentence, the probability that $k$-th word in a vocabulary is choosen by the model at $t$-th step is given by

\[p_{k}^{(t)} = \frac{\exp(l_k^{(t)})}{\sum_{i} \exp(l_{i}^{(t)})}\]where $l^{(t)}$ is a vector of logits (output of the last layer of the model). After we randomly sample whitelist $W$ of size $\gamma |V|$ from the set of vocabulary of size $|V|$, we add $\delta$ to each whitelist logit and sample the next word using the watermarked distribution

\[p_{k}^{(t)} = \begin{cases} \frac{\exp(l_{k}^{(t)} + \delta)}{\sum_{i\in B} \exp(l_{i}^{(t)}) + \sum_{i \in W} \exp(l_{i}^{(t)} + \delta)} & k \in W, \\ \frac{\exp(l_{k}^{(t)})}{\sum_{i\in B} \exp(l_{i}^{(t)}) + \sum_{i \in W} \exp(l_{i}^{(t)} + \delta)} & k \in B. \end{cases}\]This does not affect the quality of the generated sentence too much in the following sence. When a $k$-th word is highly likely and $p_{k}^{(t)} \approx 1$, then the logit $l_k^{(t)}$ is much larger than others, and this will remain the largest regardless of whether it is blacklisted or not. If not, there are many comparably large logits to choose from, and the soft watermarking has a large impact on the sampling distribution, strongly biasing the output towards the whitelist. They also suggest an algorithm to make watermarking private (see Algorithm 3 of the paper).

Theoretical analysis

The authors also provide some theoretical analysis of the soft watermark. In Theorem 4.2, they give a lower (resp. upper) bound of the expected value (resp. variance) of the number of whitelist words in a generated sentence in terms of spike entropy. In Theorem 4.3, they show that expected perplexity (which measure unlikeliness of the generated sentence) of a word generated by watermarked model is bounded by a constant multiple of the perplexity of the original model (where the actual constant is $1 + (\exp(\delta)-1)\gamma$).

Attacks

It is possible for a user to attack the watermark and avoid detection. Three types of attacks are considered: insertion (add blacklist words), deletion (remove whitelist words), and substitution (replace whitelist words into blacklist words). Here are the list of categories of attacks the author considered and ways to mitigate them.

-

Paraphrasing Attacks: Manually paraphrase sentences, which is impractical in general. Also, paraphrasing only a small amount of words still triggers watermark detection as I mentioned above.

-

Discreet Attacks: Attackers can add typos like dummy whitespaces or misspells. Such a typo is easy to be normalized, and also adding typos would degrade the quality of sentences.

-

Homoglyph and Zero-Width Attacks: Attackers replace some characters with equivalent ones but different unicodes. This can be also easily normalized.

-

Generative Attacks: Attackers generate sentences with large language models with certain prompts that thange its output in a predictable and easily reversible way. For example, we can let (Chat)GPT to add emoji after every words, then remove them afterwards. These attacks require a strong LM and also increases the cost of text generation. It may also possible to defend it by including negative examples of such prompts during fine-tuning.

machine-learning