Interesting applications of p-adic numbers

In this post, we will see some interesting applications of $p$-adic numbers. We will assume that readers are familiar with $p$-adic numbers and their basic properties.

Monsky’s theorem

One of my favorite application of $p$-adic numbers is the following theorem:

Theorem (Monsky). Assume that a unit square is partitioned by triangles of equal area. Then the number of triangles is even.

It does not seem to be related to $p$-adic numbers at all. However, as far as I know, the only known proof (by Monsky) uses $2$-adic norm as follows.

Proof. We will use two lemmas. One is about extending $p$-adic norm to finitely generated fields (from Pete L. Clark’s answer on MO):

Lemma. Let $K = \mathbb{Q}(t_1, \dots, t_n)$ be a finitely generated field over $\mathbb{Q}$ (where each $t_i$ is either algebraic or transcendental). Then the $p$-adic norm $|\cdot|_p$ can be extended to $K$.

Proof of Lemma. It is enough to show for an extension generated by single element, i.e. $K =F(t)$ for a finitely generated field $F$ (with $p$-adic norm on it) and some $t$. When $t$ is algebraic, we can extend the norm as

\[|\alpha|_K := |N_{K/F}(\alpha)|_{F}^{1/[K:F]}\]where $N_{K/F}(\alpha)$ is defined as a determinant of the multiplication map $m_{\alpha}: K \to K, x \mapsto \alpha x$.

When $t$ is transcendental, we first endow $F[t]$ with Gauss norm

\[|a_n t^n + a_{n-1} t^{n-1} + \cdots + a_0| = \max_i |a_i|_F\]and extend to $K = F(t)$ by multiplicativity. $\square$

The other lemma we need is Sperner’s lemma. There are several versions of the lemma, and we will use the following version. We will use the lemma without proof.

Lemma 2. (Sperner) Let $P$ be a polygon and consider a triangulation of this polygon. Color each vertex of this triangulation by one of the three colors red, blue, and green. Then the number of complete triangles (triangles with vertices of 3 different colors) is equal to the number of red-blue edges (resp. blue-green edges or green-red edges) on the boundary of the polygon modulo 2. Especially, when there are odd number of red-blue (resp. blue-green or green-red) edges on the boundary, then there exists at least one complete triangle.

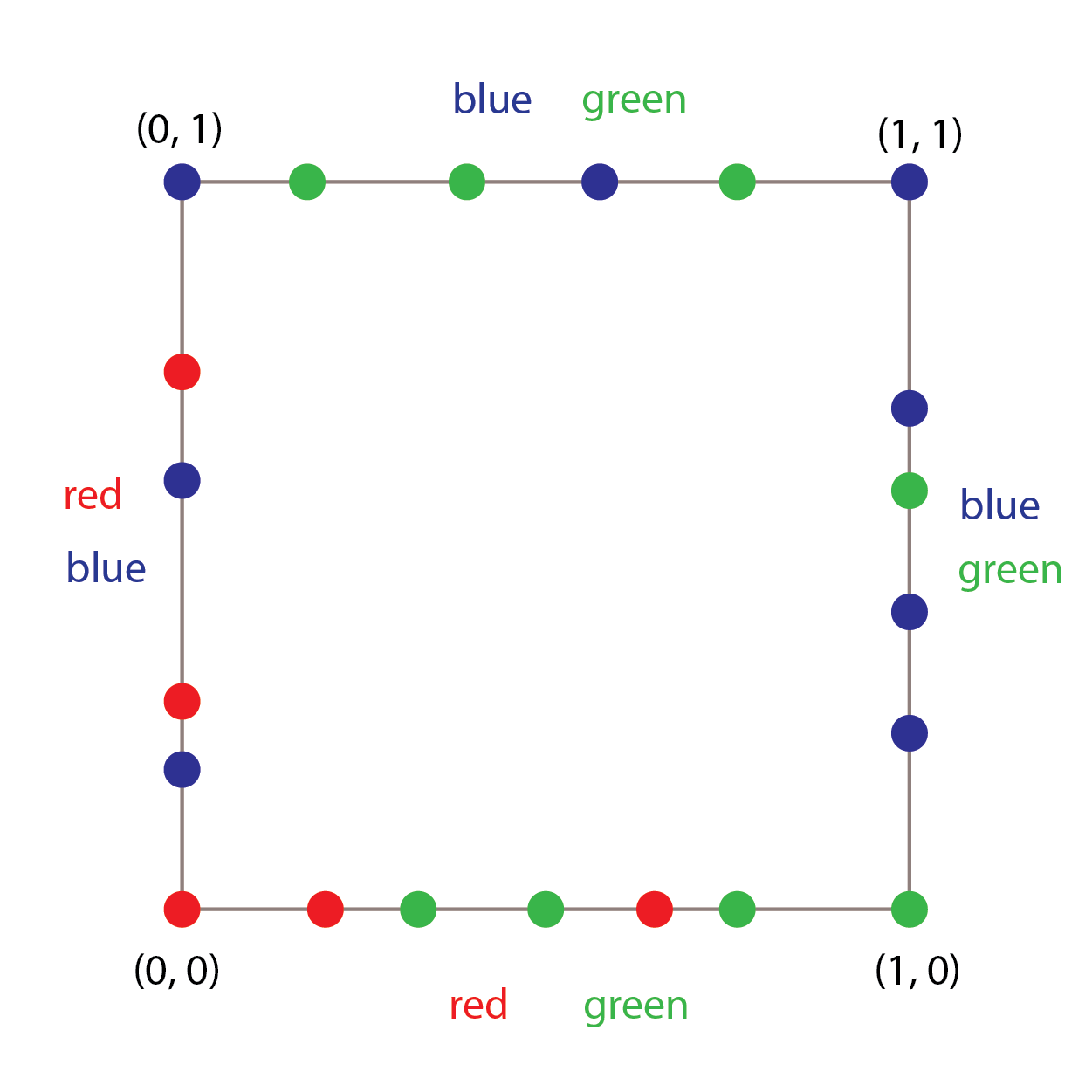

Now we prove the main theorem. Divide a square into $n$ triangles with same areas, and let $K$ be a field obtained by adjoining all the $x$ and $y$-coordinates of verticies of triangles to $\mathbb{Q}$. By Lemma 1, we can extend $2$-adic norm on $\mathbb{Q}$ to $K$, denote as $|\cdot|_2$. We will color the vertices of triangles as follows: for a given point $(x, y)\in K^2$, color it with red if $|x|_2 < 1$ and $|y|_2 < 1$, blue if $|x|_2 \leq |y|_2$ and $|y|_2\geq 1$, and green if $|x|_2 > |y|_2$ and $|x|_2\geq 1$. Then each edge can only contain at most two colors. The following figure shows how the each edge and vertex of the square can be colored.

Now one can show that red-blue edges can only occur on the left side of the square, and there should be odd number of them (see how the number changes as you add red or blue points on the left side). Hence, by Lemma 2, we can find a complete triangle where all the vertices have different colors. Let $(x_{r}, y_{r}), (x_{b}, y_{b}), (x_{g}, y_{g})$ be the coordinates of the complete triangle with red, blue, and green colors. The area $A$ of the triangle is equal to

\[\frac{(x_g - x_r)(y_b - y_r) - (x_b - x_r)(y_g - y_r)}{2} = \frac{1}{n}.\]By definition of the coloring, we have

\[\begin{align*} |x_g| \geq 1, |x_r| < 1 &\Rightarrow |x_g - x_r| = |x_g| \\ |y_b| \geq 1, |y_r| < 1 &\Rightarrow |y_b - y_r| = |y_b| \\ |x_b| \leq |y_b|, |y_b| \geq 1, |x_r| < 1 &\Rightarrow |x_b - x_r| \leq |y_b| \\ |x_g| > |y_g|, |x_g| \geq 1, |y_r| < 1 &\Rightarrow |y_g - y_r| < |x_g|. \end{align*}\]Also, $|(x_g - x_r)(y_b-y_r)| \neq |(x_b - x_r)(y_g - y_r)|$, since both $|y_b|$ and $|x_g|$ are nonzero. Hence

\[|(x_g - x_r)(y_b-y_r)| =|x_g||y_b| > |(x_b - x_r)(y_g - y_r)|\]and this implies

\[\begin{align*} |A|_2 &= |1/2|_2|(x_g - x_r)(y_b - y_r) - (x_b - x_r)(y_g - y_r)|_2 \\ &= 2|x_g|_2|y_b|_2 \geq 2. \end{align*}\]Now from $A = 1/n$, we get $|n|_2 \leq 1/2$ and $n$ should be even. $\square$

Note that the original proof uses Axiom of Choice to impose $2$-adic norm on $\mathbb{C}$ via $\mathbb{C} \simeq \mathbb{C}_2$. However, as we did above (using Lemma 1), we don’t need AC to prove the theorem - imposing $2$-adic valuation on $K$ is enough.

Skolem-Mahler-Lech theorem

Consider a sequence ${a_n}$ defined by

\[a_0 = a_1 = 1, \quad a_{n+2} = a_{n+1} - a_{n}.\]If you compute first few terms of $a_n$, you will find that the sequence is periodic as

\[1, 1, 0, -1, -1, 0, 1, 1, 0, -1,-1, 0, \dots\]and the zero set of $a_n$ (set of $n$ with $a_n = 0$) is ${n:n\equiv 2\,\mathrm{mod}\,3}$.

Consider another sequence ${b_n}$ given as

\[b_n = 2b_{n-1} - 4b_{n-2} + 8b_{n-3}\]with $b_0 = b_1 = 1$ and $b_2 = -2$. Then one can show that $b_n = 0$ if and only if $n\equiv 3\,(\mathrm{mod}\, 4)$. In both cases, the zero set of sequence are periodic. Skolem-Mahler-Lech theorem tells us that this is true in general:

Theorem (Skolem-Mahler-Lech). The zero set of a linear recurrence sequence is eventually periodic.

In this post, we will only consider integer sequences, which was the scope of the original result by Skolem (it is generalized further by Mahler and Lech for algebraic numbers and characteristic 0 fields). Surprisingly, all the known proofs uses $p$-adic integers. Here we will provide a proof by Hansel, which is stolen from Terrence Tao’s blog post.

Proof. Let ${x_n}$ be an integer sequence defined recursively as $x_n = a_1 x_{n-1} + \cdots + a_{d} x_{n-d}$ with $a_i \in \mathbb{Z}$. We can assume that $a_d \neq 0$. Then

\[\begin{pmatrix} x_{n+1} \\ x_{n+2} \\ \vdots \\ x_{n+d}\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ a_{d} & a_{d-1} & a_{d-2} & \cdots & a_{1} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x_n \\ x_{n+1} \\ \vdots \\ x_{n+d-1}\end{pmatrix}\]and this let us to write $x_n$ as

\[x_n = \langle A^n v, w\rangle\]for some $A \in \mathrm{GL}_{d}(\mathbb{Z})$ and $v, w\in \mathbb{Z}^d$ (we can take $A$ as the above $d\times d$ matrix, $v = (x_0, x_1, \dots, x_{d-1})^{\intercal}$ and $w = (1, 0, \dots, 0)^{\intercal}$). Choose a prime $p> 2$ that does not divide $\det(A)$, so that $A$ is also invertible modulo $p$. Then we can find $m \geq 1$ such that $A^m \equiv I \,(\mathrm{mod}\,p)$ (take $m$ to be the order of $A$ in $\mathrm{GL}_n(\mathbb{F}_p)$).

Our claim is that $m$ is the eventual period of the zero set. More precisely, for each $r = 0, 1, \dots, m-1$, we will prove that

\[\{n \geq 0: x_{mn + r} = 0\}\]is either finite or all $\mathbb{Z}_{\geq 0}$. Assume that it is infinite. Let $A^m = I + pB$ with $B \in M_{d \times d}(\mathbb{Z})$ and put

\[P(n) := x_{mn + r} = \langle A^{mn+r}v, w \rangle = \langle (I+pB)^n A^r v, w \rangle\]which is a function $P: \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z}$ that is zero for infinitely many $n$ by assumption. Since $|(I+pB)^{p^m} - I|_p \to 0$ as $m \to \infty$ (where $|M|_p := \sup_{i, j} |m_{i, j}|_p$ for $M = (m_{i, j})$), the function can be extended as $P: \mathbb{Z}_p \to \mathbb{Z}_p$. Write $P(n)$ as a formal power series

\[P(n) = \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} p^j P_j(n).\]The binomial expansion of $(I+pB)^n$ is

\[(I+pB)^n = \sum_{k \geq 0} \binom{n}{k} (pB)^k = \sum_{\geq 0} n(n-1)\cdots (n-k+1) \frac{p^k}{k!} B^k.\]Now we have

\[\begin{align*} v_p\left(\frac{p^k}{k!}\right) &= k - v_p(k!) = k - \left(\left\lfloor \frac{k}{p} \right\rfloor + \left\lfloor \frac{k}{p^2}\right\rfloor + \cdots \right) \\ &> k - \left(\frac{k}{p} + \frac{k}{p^2} + \cdots\right) = \left(\frac{p-2}{p-1}\right) k \xrightarrow{k\to\infty} \infty \end{align*}\](note that we assumed $p> 2$). This implies that each of $P_j$ can be build using only finitely many of the terms in the binomial expansion. Hence $P: \mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z}$ extends continuously to a function $P:\mathbb{Z}_p \to \mathbb{Z}_p$ such that each $n\mapsto P(n) \,(\mathrm{mod}\,p^j)$ is a polynomial in $n$ for all $j$. In other words, it is a uniform limit of polynomials.

Now, we will show that $P$ is identically zero. If $n_0$ is a zero of $P$, then we can factor $P(n)$ as

\[P(n) = (n - n_0)Q(n) = (n - n_0) (Q_0(n) + pQ_1(n) + p^2 Q_2(n) + \cdots)\]for some continuous $Q: \mathbb{Z}_p \to \mathbb{Z}_p$. Then $P_0(n) = (n - n_0)Q_0(n)$, i.e. $n_0$ is also a zero of the constant term $P_0(n)$ which is a polynomial. Since $P$ has infinitely many zeros, $P_0$ should vanish and $P(n)$ is divisible by $p$. By repeating the same argument, $P$ should be divisible by arbitrary power of $p$, which implies $P = 0$. This concludes the proof. $\square$

Note that the theorem is false in characteristic $p$: consider the sequence ${a_n}$ in $\mathbb{F}_p(x)$ defined as

\[a_n = (2x+2)a_{n-1} - (x^2 + 3x + 1)a_{n-2} + (x^2 + x)a_{n-3}.\]with initial conditions $a_0 = -1, a_1 = 0, a_2 = 2x^2$. This sequence is nothing but

\[a_n = (x+1)^n - x^n - 1,\]and we have $a_{p^k} = 0$ for all $k\geq 0$, which can’t be a finite union of arithmetic progressions. Harm Derksen proved that this is essentially the only way where the theorem could fail in positive characteristic.

$\pi$ and $e$ are transcendental

(This section follows Matt Baker’s blog post.) Another striking application of $p$-adic numbers is that $\pi$ and $e$ (and many more) are trancendental. More generally, Bezvin and Robba proposed an alternative proof of the following Lindemann-Weierstrass theorem:

Theorem (Lindemann-Weierstras). Let $\alpha_1, \dots, \alpha_n$ be distinct algebraic numbers. Then $e^{\alpha_1}, \dots, e^{\alpha_n}$ are linearly independent over $\overline{\mathbb{Q}}$.

As a corollary, if $\alpha$ is an algebraic number, then $e^\alpha$ is trancendental. From this, trancendentality of $\pi$ and $e$ directly follows ($e^{\pi i} = -1$ and $e^1 = e$). Bezvin and Robba’s first show that the theorem is equivalent to the following statement:1

Theorem (Bezvin-Robba). Let $\mathcal{F}_{\mathbb{Q}} = \frac{1}{x} \mathbb{Q}[[\frac{1}{x}]]$ be a ring of formal power series vanish at infinity. Define $\mathcal{D}: \mathcal{F}_{\mathbb{Q}} \to \mathcal{F}_{\mathbb{Q}}$ be a differential operator defined as $\mathcal{D}(v):= v + v’$. If $v \in \mathcal{F}_{\mathbb{Q}}$ is analytic at infinity and $\mathcal{D}(v)$ is a rational function, then $v$ is also rational.

Although Bezvin and Robba showed that two statements (theorems) are equivalent, I will only introduce the proof of (B-R $\Rightarrow$ L-W), which is enough for our purpose. See the above blog post for the proof of the other direction.

Proof (B-R $\Rightarrow$ L-W). Assume that L-W theorem is false, so that there exists distinct algebraic numbers $\alpha_1, \dots, \alpha_n$ and nonzero algebraic numbers $\beta_1, \dots, \beta_n$ such that $\beta_1 e^{\alpha_1} + \cdots + \beta_{n} e^{\alpha_{n}} = 0$. Let $f(z) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \beta_{n} e^{\alpha_{n} z}$, so that $f(1) = 0$ by assumption. By replacing $f(z)$ with the product of its Galois conjugates $\sum_{i=1}^{n} \sigma(\beta_i) e^{\sigma(\alpha_i)z}$, we can assume that the power series expansion of $f(z)$ has $\mathbb{Q}$-coefficients. Now, consider the Laplace transform of $f$, which is $\mathcal{L}(f) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{\beta_i}{1 - \alpha_i z}$. Since $f(1) = 0$ and $\alpha_i$ are distinct, we have $n\geq 2$ and at least one $\alpha_i$ should be nonzero, so $f(z)$ has at least one simple pole. Now we need a following lemma, which we will use without proof:

Lemma. $f(z) \in \mathbb{C}[[z]]$ defines an entire function of exponential growth (i.e. $|f(z)| \leq C_1 e^{C_2|z|}$ for some constants $C_1, C_2$) if and only if $\mathcal{L}(f)$ is analytic at infinity.

Let $g(z) := \frac{f(z)}{z-1}$, which is analytic by the assumption $f(1) = 0$. Hence, by the above Lemma, $v:=\mathcal{L}(g) \in \frac{1}{x} \mathbb{C}[[\frac{1}{x}]]$ is analytic at infinity. By the way, direct computation shows that $\mathcal{L}(f) = \mathcal{D}(v)$, hence it has a simple pole. On the other hand, one can show that $\mathcal{D}(v)$ cannot have a simple pole if $v$ is a rational function, which leads to a contradiction. $\square$

Now our goal is reduced to the above rationality statement. There are many related theorems, starting from the following observation by Borel: if $f(z) = \sum_{n\geq 0} a_n z^n \in \mathbb{Z}[[x]]$ defines an analytic function on a closed disc of radius $R > 1$ centered at $0$ in $\mathbb{C}$, then $f(z)$ is a polynomial. This easily follows from Cauchy’s integral formula: $|a_n| \leq \frac{M}{2\pi R^{n+1}}$ for $M = \sup_{|z| \leq R} |f(z)|$, and taking $n\to\infty$ shows that $a_n =0$ for sufficiently large $n$. Borel generalized this to the following theorem:

Theorem (Borel) If $f(z) = \sum_{n\geq 0} a_n z^n \in \mathbb{Z}[[x]]$ defines a meromorphic function on a closed disc of radius $R > 1$ centered at $0$ in $\mathbb{C}$, then $f(z)$ is a rational function.

The proof of Borel’s theorem uses Kronecker’s characterization of rational functions via Kronecker-Hankel determinant (see Lemma 10 of this). Borel’s theorem is generalized in several directions, including Dwork’s $p$-adic analogue (which is used for the proof of rationality of zeta functions for curves over finite fields: see this again). For our purpose, we will use the following criterion by Bertrandias:

Theorem (Bertrandias). Let $g(z) = \sum_{n\geq 0} \frac{a_n}{z^{n+1}} \in \mathcal{F}_{\mathbb{Q}}$. Let $S$ be a finite set of places, containing the infinite places, such that

(B1) For $p \not \in S$, $|a_n|_p \leq 1$ for all $n\geq 0$.

(B2) For $p \in S$, $g(z)$ extends to a meromorphic function on the complement of a bounded set $K_v \subset \mathbb{C}_v$ (which is assumed to be a finite union of discs if $v$ is non-archimedean) and $\prod_{v\in S} \delta_{\infty}(K_v) < 1$.

Then $g(z)$ is a rational function.

Here $\delta_\infty$ is a transfinite diameter defined as

\[\delta_{\infty}(A) := \lim_{N\to\infty} \delta_{N}(A), \quad \delta_{N}(A):= \sup_{z_1, \dots, z_N \in A} \left(\prod_{i \neq j} |z_i - z_j|\right)^{\frac{1}{N(N-1)}}\]for any bounded set $A$ of a normed space. The proof of Bertrandias’ criterion is similar to that of Borel’s and Dwork’s theorem.

Now let’s prove Bezvin-Robba’s theorem using Bertrandias’ rationality criterion.

Proof (Bezvin-Robba). Let $\omega(x) = \mathcal{D}(v)(x) = v(x) + v’(x)$, which is a rational function by assumption. Expand $\omega(x)$ a partial fraction as follows:

\[\omega(x) = \sum_{i, j} \frac{c_{i, j}}{(x - \gamma_i)^j}\]where $\gamma_1, \dots, \gamma_m$ are distinct algebraic numbers. By using the formal inverse $\mathcal{D}^{-1} = (1 + \frac{d}{dx})^{-1} = \sum_{k \geq 0} (-1)^{k} \frac{d^k}{dx^k}$, $v$ has the following partial fraction expansion

\[v(x) = \sum_{i, j} c_{i, j}\sum_{k \geq 0} \binom{k+j-1}{j-1} \frac{k!}{(x - \gamma_i)^{k+j}}.\]Now let $S_1$ be a set of places of $\mathbb{Q}$ containing archimedean place such that for $p \not \in S_1$,

1) $|c_{i, j}|_p = 1 = |\gamma_j|_p$ whenever they are nonzero,

2) $|\gamma_i - \gamma_j|_p = 1$ for all $i\neq j$.

Then one can show that the coefficients of the expansion $v(x) = \sum_{n \geq 0} \frac{a_n}{x^{n+1}}$ are $p$-adic integers for all $p \not \in S_1$ (consider Laurent series expansion of $1/(x-\gamma_i)^{k+j}$ near $x = 0$). Hence the condition (B1) is satisfied for any $S$ containing $S_1$.

For (B2), note that $v(x)$ converges outside of a disc $K_p \subset \mathbb{C}_p$ of some positive radius $R_p$ for all $p \in S_1$. For $p \not \in S_1$, $v(x)$ converges in the complement of $K_p$ that is a union of discs $D_i$ centered at $\gamma_i$’s, and we can take radii of discs as $p^{-1/(p-1)}$ since the radius of convergence of $\sum_{k\geq 0} k! x^k$ is $p^{1/(p-1)}$. Since the radius of convergence is smaller than 1, the discs are disjoint by second assumption on $S_1$. Now, the transfinite diameter of $K_p$ becomes:

Lemma. We have

\[\delta_{\infty}(K_p) = \delta_{\infty}\left(\bigcup_{i=1}^{m} D_i\right) = p^{-\frac{1}{m(p-1)}}.\]

Let’s postpone the proof of the lemma for a moment. Since $\sum_{p} \frac{\log p}{p}$ diverges, the infinite product $\prod_{p\not \in S_{1}} \delta_{\infty}(K_p)$ diverges to zero, hence there exists a finite set $S$ containing $S_1$ such that $\prod_{p \not \in S} \delta_{\infty}(K_p) < 1$, and such a choice of $S$ satisfies both (B1) and (B2). Thus $v(x)$ is a rational function. $\square$

Proof of Lemma. First, note that if $z_i$ and $z_j$ are not in the same disk, then the triangle inequality gives $|z_i - z_j| \leq \max{|z_i - \gamma_i|, |\gamma_i - \gamma_j|, |\gamma_j - z_j|}$, and this implies $|z_i - z_j| = 1$ since $|\gamma_i - \gamma_j| = 1$ and $|z_i - \gamma_i|, |z_j - \gamma_j| \leq p^{-1/(p-1)} < 1$. If $z_i$ and $z_j$ lies in the same disk, then $|z_i - z_j| \leq \max{|z_i - \gamma_i|, |\gamma_i - z_j|} \leq p^{-1/(p-1)}$. Now, let $z_1, \dots, z_N$ be points in $K_p$, and each $D_i$ contains $k_i$ points of them with $k_1 + \cdots + k_m = N$. Then

\[\begin{align*} \delta_N(K_p) &\leq (p^{-\frac{1}{p-1}})^{\left(\frac{k_1(k_1 -1)}{2} + \cdots + \frac{k_m(k_m -1)}{2}\right) \frac{2}{N(N-1)}} \\ &= (p^{-\frac{1}{p-1}})^{(k_1^2 + \cdots + k_m^2 - N)\cdot \frac{1}{N(N-1)}} \\ &\leq (p^{-\frac{1}{p-1}})^{\left(\frac{N^2}{m} - N\right)\frac{1}{N(N-1)}} \end{align*}\]where the second inequality follows from $k_1^2 +\cdots + k_m^2 \geq \frac{N^2}{m}$ (Cauchy-Schwartz). Taking the limit $N\to\infty$ gives $\delta_{\infty}(K_p) \leq p^{-\frac{1}{m(p-1)}}$.

For the other direction, assume that $N = mk$ is a multiple of $m$. Now we choose $k$ points $z_{i, 1}, \dots, z_{i, k}$ in each disk $D_i$ as $z_{i, j} = \gamma_i + p^{-1/(p-1)} \zeta_M^j$, where $M$ is an integer coprime to $p$ and $\zeta_M \in \mathbb{C}_p$ is $M$-th root of unity. Then one can show that $|z_{i, j} - z_{i, j’}| = p^{-1/(p-1)}$ for any $j \neq j’$, and this gives a lower bound

\[\delta_{mk}(K_p) \geq (p^{-\frac{1}{p-1}})^{\frac{mk(k-1)}{2} \frac{2}{N(N-1)}} = (p^{-\frac{1}{p-1}})^{\frac{N/m - 1}{N-1}}\]where the RHS converges to $p^{-1/(m(p-1))}$ as $N\to\infty$. This gives $\delta_\infty(K_p) \geq p^{-1/(m(p-1))}$ and completes the proof. $\square$

Other applications

Here are some list of other interesting applications of $p$-adic numbers:

- Structure of $(\mathbb{Z}/p^n\mathbb{Z})^\times$. Use $p$-adic exponential and logarithm to show that they are cyclic (for odd $p$ - when $p=2$ then $(\mathbb{Z}/2^k\mathbb{Z})^\times$ it is a product of two cyclic groups). See this note.

- Galois group of certain polynomials. Coleman showed that the Galois group of a splitting field of truncated exponential polynomial $f_n(x) = \sum_{k=0}^{n} \frac{x^k}{k!}$ is $S_n$ if $4\nmid n$ and $A_n$ otherwise, using Newton polygons. See this blog post by Baker.

- Complex dynamics. See this MO answer by Silverman and also the original paper by Baker-DeMarco. Although the statement is about dynamics over complex numbers, proof uses equidistribution theorem on non-archimedean Berkovich spaces.

- Cryptanalysis. See Klapper and Goresky’s paper on attacking stream ciphers using 2-adic numbers.

-

As it mentioned in Matt Baker’s blog post, this statement is slightly different from the original one from Bezvin-Robba, which are essentially the same via simple transformation. ↩

math