A progress on Conway-Soifer conjecture

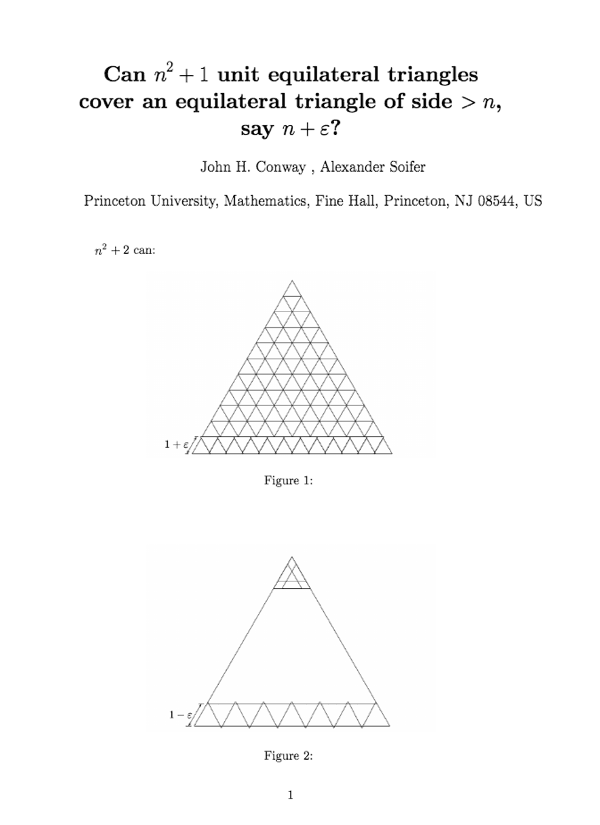

I recently wrote a paper on the Conway-Soifer conjecture with my friend Jineon Baek. The paper by Conway and Soifer is famous for holding the best record for the world’s shortest paper ever:

One can read Soifer’s article on the history of the paper and some progress on the problem itself. In our paper, we proved that the conjecture holds if we restrict our attention to the triangles with sides parallel to the large triangle (i.e., homothetic). The idea is new and considers some auxiliary function that measures the length of the line segments on $y = t$ covered by triangles. We also show that $\epsilon = 1 / (n+1)$ is the largest ϵ where we can cover the equilateral triangle with lengths $n + \epsilon$ with $n^2 + 2$ triangles. A slight tweak of the proof gives a similar result with $n^2 + 3$ triangles and $\epsilon = 1 / n$. Unfortunately, it is unavoidable to remove homothetic assumptions to make our proof work.

Since the paper is already on arXiv, you can read it yourself (it’s short - only eight pages), and I’m not going to explain the proof in detail. Instead, I’ll share some stories on writing that paper.

Jin introduced me the original conjecture about 1~2 years ago, and I also saw the image of the paper above somewhere on the internet a few years ago (although I wasn’t that into the problem at the moment). Instead of directly attacking the problem, we first considered the simplified problem, the version we solved in our paper.

$n = 2$ case is easy: click the triangle below for the proof (also, do not read our paper before you try it yourself since it also introduces a proof for $n = 2$ cases). This case also appeared as Soifer’s math contest problem.

Proof when n = 2

Consider three vertices and three midpoints of the large triangle with lengths $2 + \epsilon$. Each unit equilateral triangle can only cover one of these points, so we need at least $6 = 2^2 + 2$ triangles to cover all.So you can even solve the original conjecture without any assumptions on homothety in this case. How about $n = 3$? We spent some time on this case (not only the restricted case but also trying to solve the original conjecture for $n = 3$). I found a simple proof of the conjecture with the restriction on homothety (again, spoiler alert before you open it).

Proof when n = 3, homothetic case

It is enough to show that we can't cover a regular hexagon of length $1 + \epsilon$ with $7$ unit equilateral (homothetic) triangles. If the unit triangles are all homothetic, and we can observe that the maximum length of the segments on the perimeter of the hexagon that it can cover is at most one, so we need at least seven triangles to cover the perimeter. However, these won't be able to cover the center of the hexagon. Hence, we need an extra piece to cover all: a total of $8 = 3^2 + 2 - 3$ triangles.Note that the problem without the restriction is still unsolved, and the 50-dollar prize is waiting for the solution (see this MO post). We tried to generalize this proof to other $n$’s (with the homothety assumption again) by defining some nice measure on the triangle, but it didn’t go well. In fact, a fractional covering exists when $n = 4$, which rules out the existence of such proofs for general $n$. A few weeks later, Jin came up with the brilliant idea, and that’s it.

There are some related open problems that we have yet to mention in the paper.

-

Can we find a nice formula for the maximal possible $\epsilon = \epsilon(n, m)$ for given $n$ and $1 \leq m \leq 2n$, such that one can cover the equilateral triangle of length $n + \epsilon$ with $n^2 + m$ unit equilateral homothetic triangles? Our results cover $m = 1, 2, 3$ cases and are not known in general. We don’t even have any conjecture for that.

-

Higher dimensional generalization. I firmly believe that our method can be generalized to the problem covering $d$-dimensional simplex of length $n + \epsilon$ with $n^d + m$ unit $d$-dimensional simplexes homothetic to the large one. Michael Todd considered such a generalization and propose a covering with $(n+1)^d + (n-1)^d - n^d$ simplexes (for $d > 1$), when $\epsilon < 1 / (n+2)$. The problem is more challenging for the obvious reason: imagining a higher dimension is harder than a lower dimension.

-

Dual problem. Instead of covering the triangle, we can consider packing the triangle with smaller triangles without any overlaps.

-

It seems that something deeper is hiding in the proof. The function $f_T(t) = \sum_{n \in \mathbb{Z}} \tilde{f}_T(t + n)$ we used coincides with the auxiliary function used in the proof of Poisson summation formula. Is there any Fourier theory going on here?

Also, while writing the manuscript, we worked on our private GitHub repository, which was super helpful. I haven’t done this before (I only used Overleaf for coworking on paper), but using GitHub can be more organized by making issues and pull requests. I highly recommend it if you have never done it before. (Overleaf also provides a syncing feature with GitHub, though.)

The paper will appear soon on AMM (the same journal as the original paper by Conway and Soifer). Let me know if you are interested in the paper and want the most recent and cleaner version.

Tags:math