Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations

There are recent initiatives, including IMO Grand Challenge and AIMO that seek AI solving international mathematical olympiad problems and win a gold medal. Although there is much progress in theorem proving with AI, it can only solve some basic K12 or undergraduate calculus problems and needs to be better to solve math olympiad problems or research-level problems. It can help mathematical research by providing new insights based on the existing data, but AI itself cannot prove any useful theorems.

In the recent work I will introduce here, DeepMind makes significant progress on the IMO challenge by achieving (almost) gold medal-level scores for geometry problems. The AlphaGeometry is published in Nature. We will see what made it possible and share some of my ideas on the work. Note that there is an official blog article introducing AlphaGeometry, so I will try to cover things that are not introduced in the article.

Olympiad geometry problems

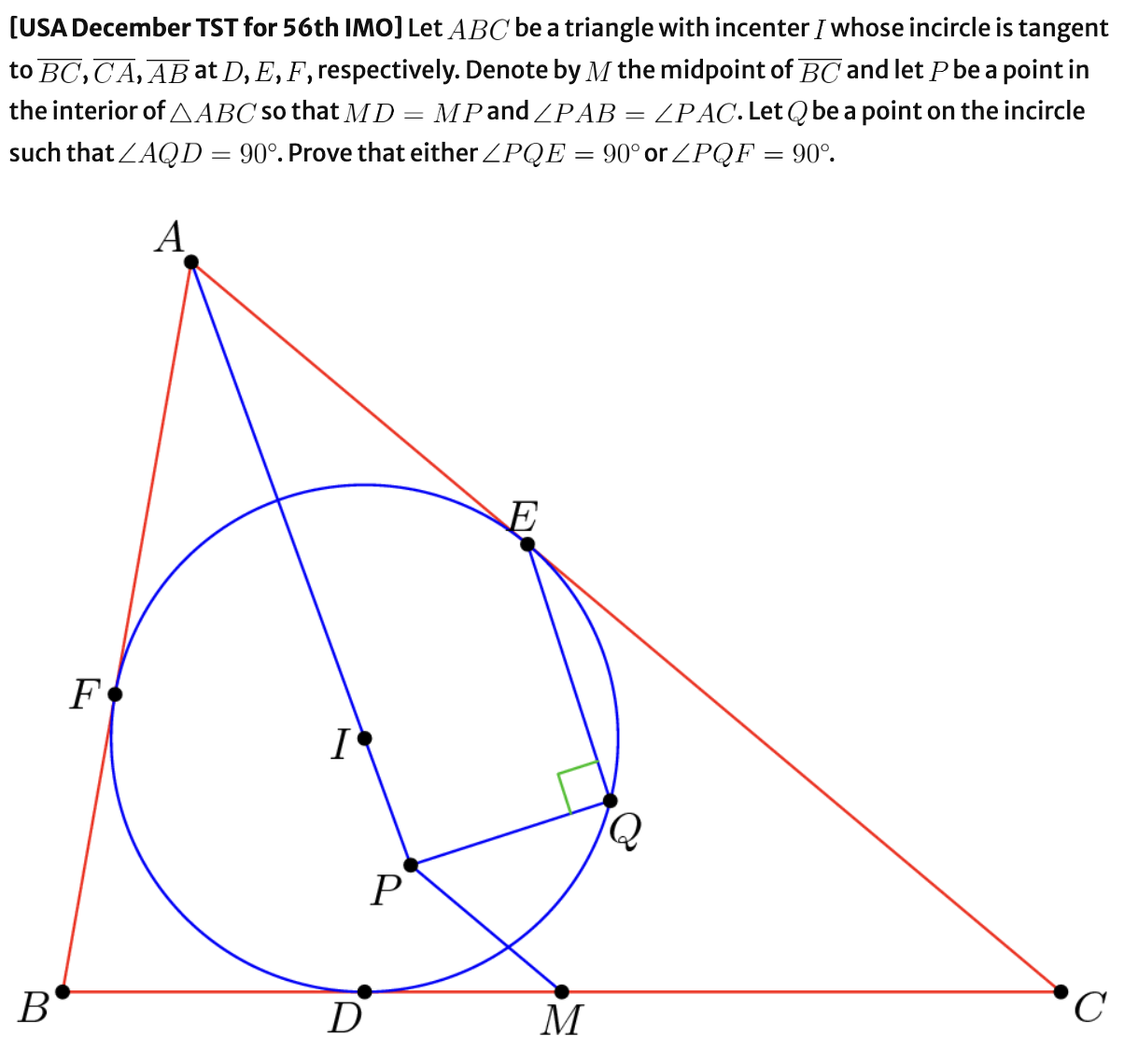

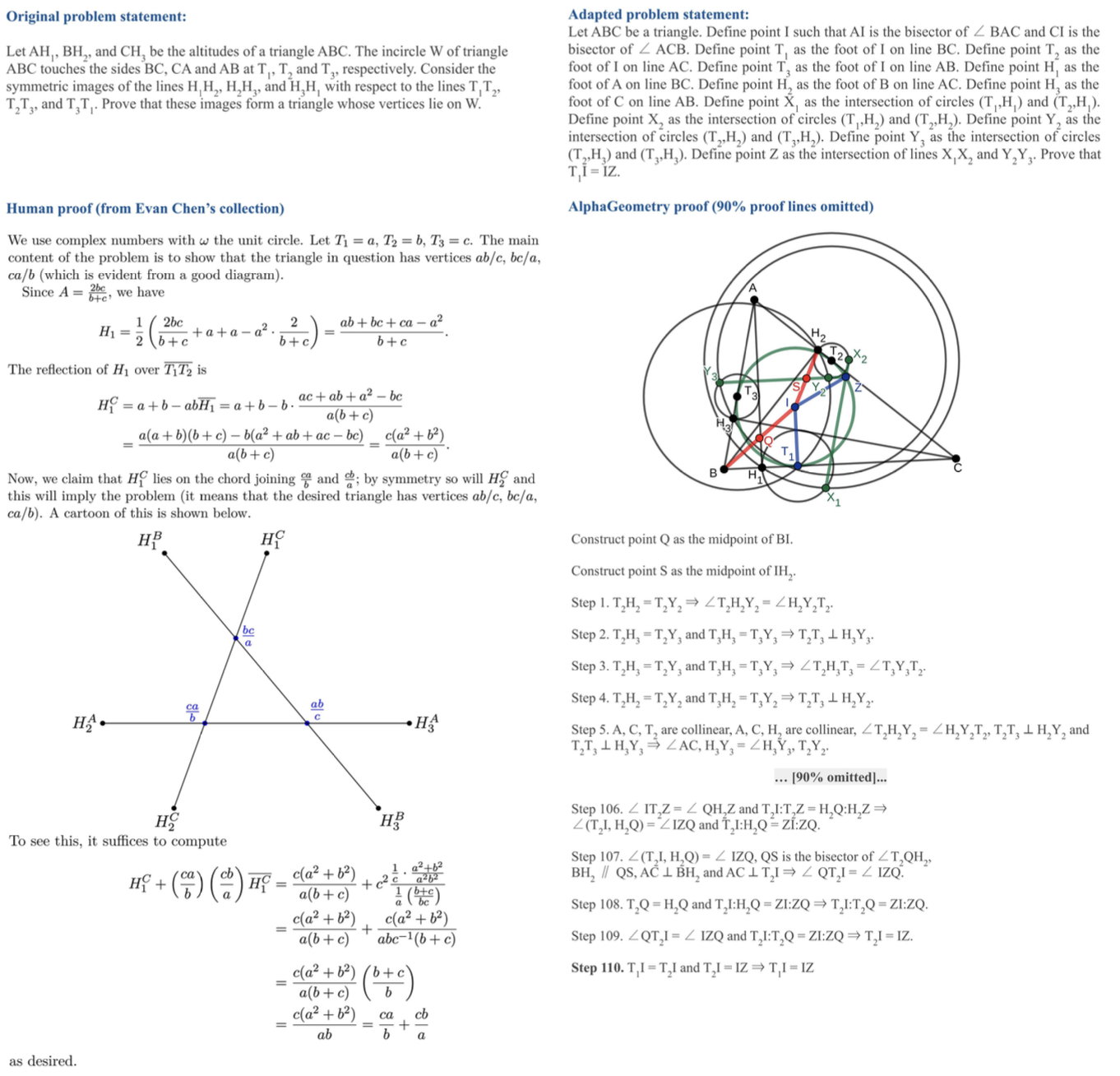

I have a little bit of experience in math competitions and olympiads, but always not good at it though. Especially, I was really bad at solving the olympiad geometry problems in general. Usually, most of the hard geometry problems require us to find some auxilliary lines or circles that help to find a solution of the problem, which is not trivial to do and requires some training. For example, here’s a problem from Evan Chen’s blog post.

You can find how Evan made the problem in his blog post. In particular, many auxiliary points and lines are used in the construction, which are removed in the actual problem.

Some possible approaches

How can we solve math problems automatically? We may use AI. AI (or Machine Learning / Deep Learning - I do not like the term ‘AI’ that much) requires data for training. Solving classification or regression problems with AI requires some input and target pairs (e.g., images and labels or study records and exam scores). We especially need high-quality data, as much as possible, to get a high-performance model in it. Hence, if we want to train a model (whatever it is - LLM or just some classical ML algorithms) that solves olympiad geometry problems, we need data that may contain pairs of problems and solutions. Although many of the problems are available online (look at any math contest problems that are publicly available. For example, you can find all the previous IMO problems here.), finding the corresponding solutions that are good enough might be challenging. One can build such data by hiring some smart high school students and olympiad alums to generate the solutions. However, it needs a lot of time and still requires post-processing steps to make them understandable by computers.

Also, data insufficiency is one of many problems. Even if we have sufficient training data, building a model that solves nontrivial math problems (especially competition problems in this case) is much more complicated than classifying images into ten categories. One needs to generate a complete solution (proof) of the correct problem (note that GPT-3.5 usually gives ridiculous statements when I ask mathematical questions about it).

In the paper, the baseline work by Wu is essentially about the Tarski’s axioms. Alfred Tarski presented this axiom in 1926, which says that all Euclidean geometry problems can be described as first-order sentences in Tarski’s axiom. Tarski especially proved that the first-order theory of Euclidean geometry is consistent, complete, and decidable. Every sentence in its language is either provable or disprovable from the axioms, and we have an algorithm that decides whether any given sentence is provable or not (from Wikipedia above). You can find more detailed discussions in this Buzzard’s MO question and answers.

However, note that math competitions only provide a limited amount of time - for example, you have only nine hours to solve given six problems in IMO. It’s why Wu’s method stays as a baseline compared to AlphaGeometry. They mentioned that Wu’s method (or other computer algebra methods like Gröbner basis) can solve any problem in 48 hours.

How AlphaGeometry works

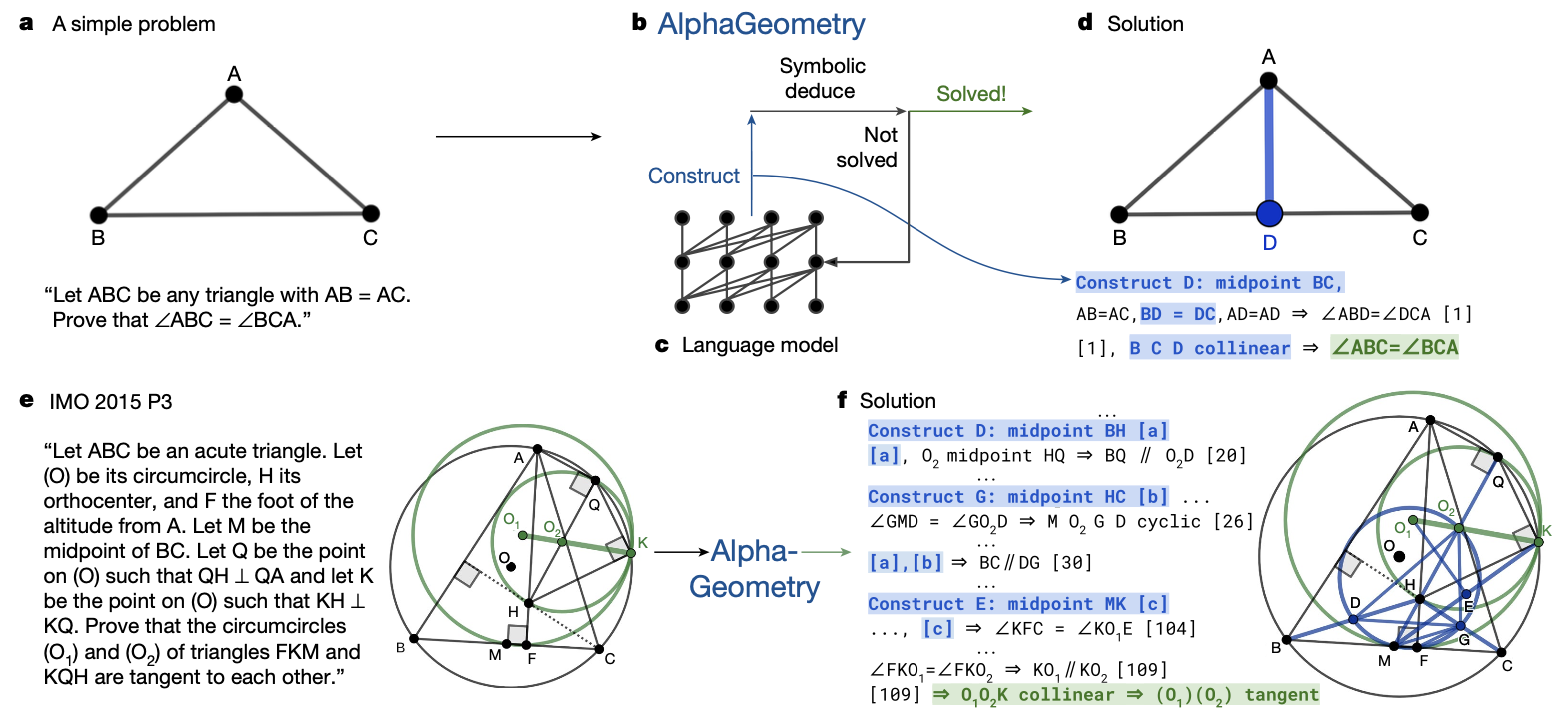

So, what did AlphaGeometry actually do? How did they beat Wu’s method and all the other baselines? First, it uses both the symbolic engine and the natural language model. The symbolic method (like Tarski’s axioms) guarantees a correct solution, but it usually takes much time and may need to be better at timed exams. In contrast, (large) language models (or maybe deep neural networks in general) are good at finding patterns in data and giving outputs quickly but are only sometimes correct.

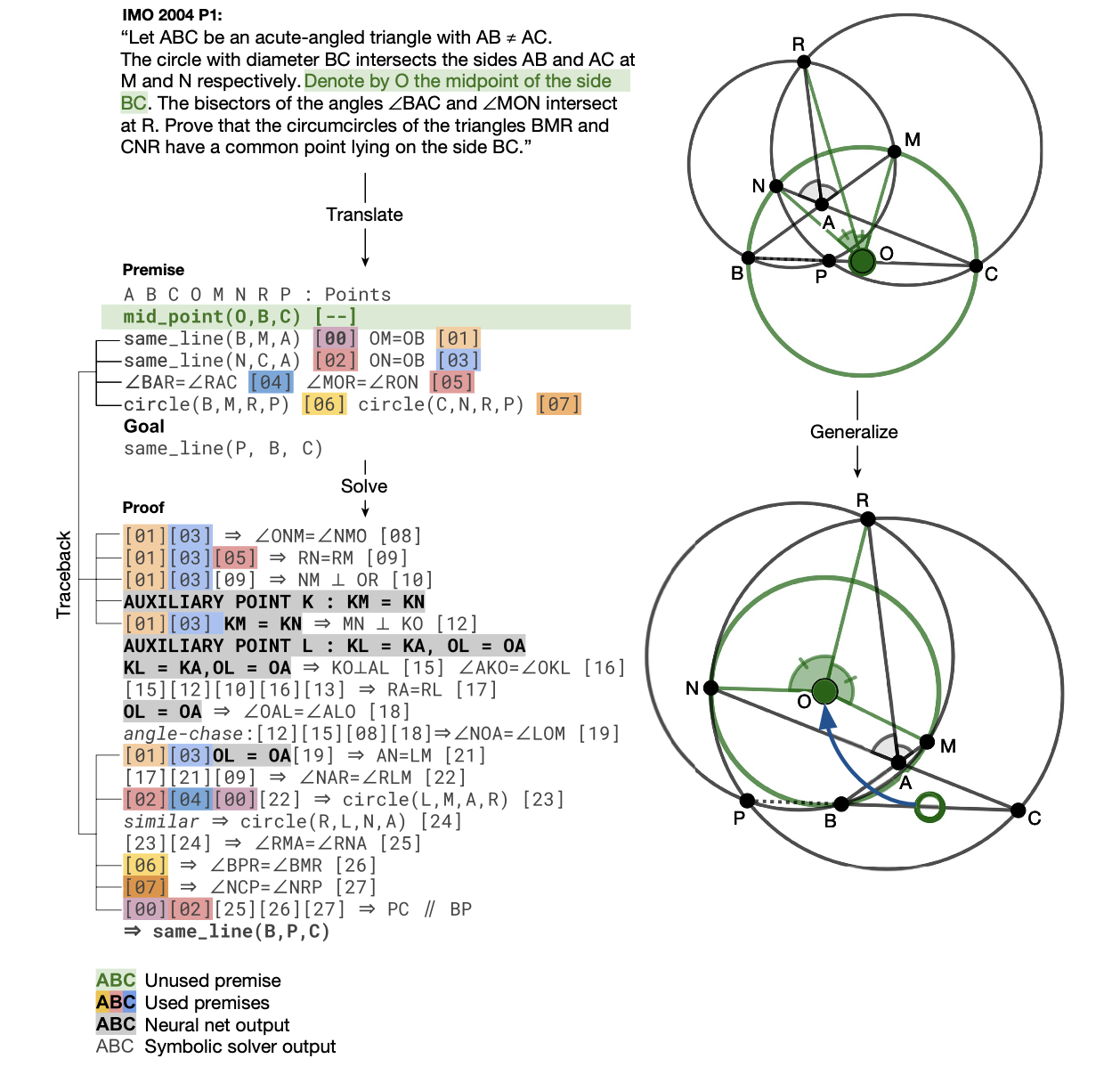

AlphaGeometry utilizes the advantages of both approaches. In particular, language models are trained to provide ideas for constructing auxiliary points/lines/circles, which often become a key to solving olympiad geometry problems, as mentioned. This does not need to be correct - it is an idea or starting point to approach a problem. Then, the symbolic engine deduces a solution based on the given problem and auxiliary inputs by language models. For example, the three auxiliary midpoints produced by language models essentially help the symbolic engine complete the solution. Note that they (symbolic engine and language model) are not executed in parallel - instead, they take turns.

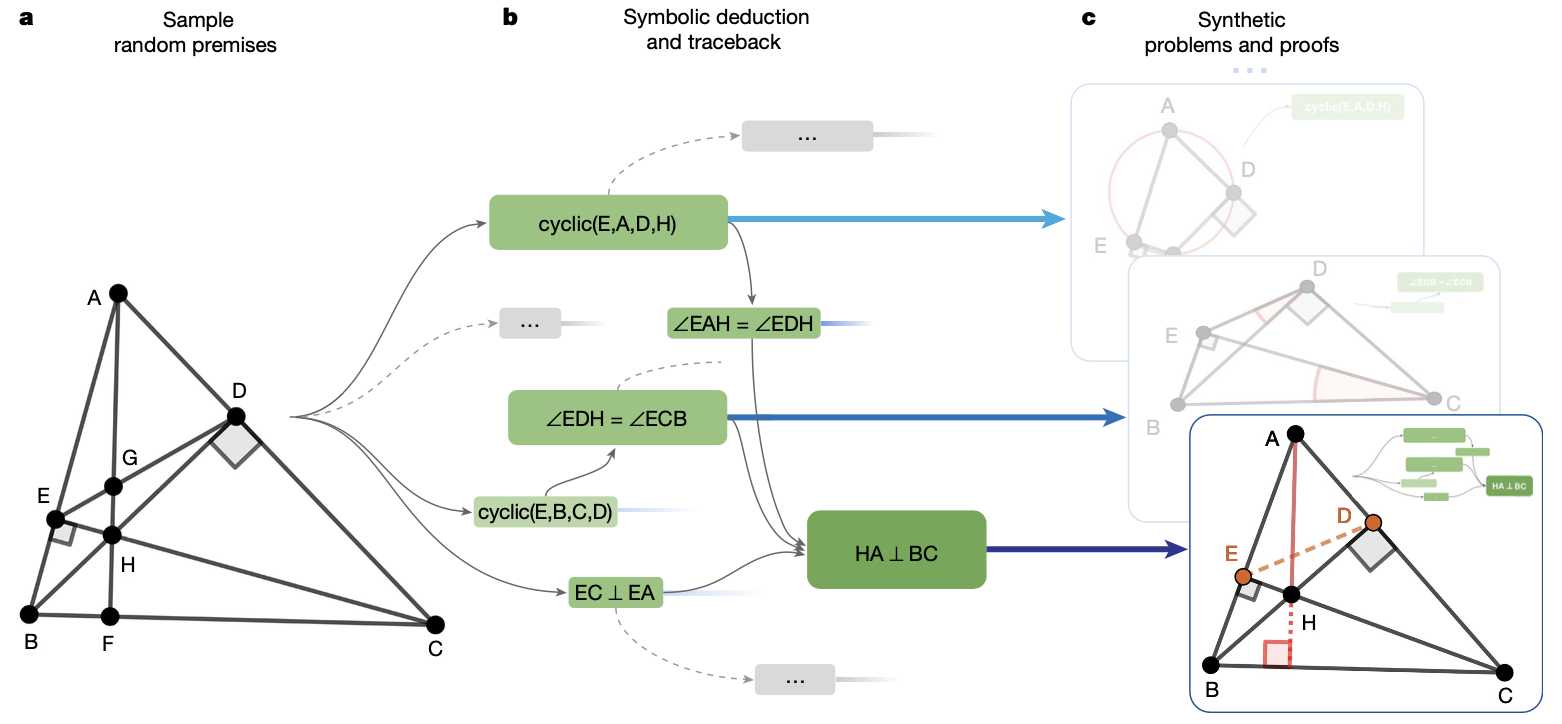

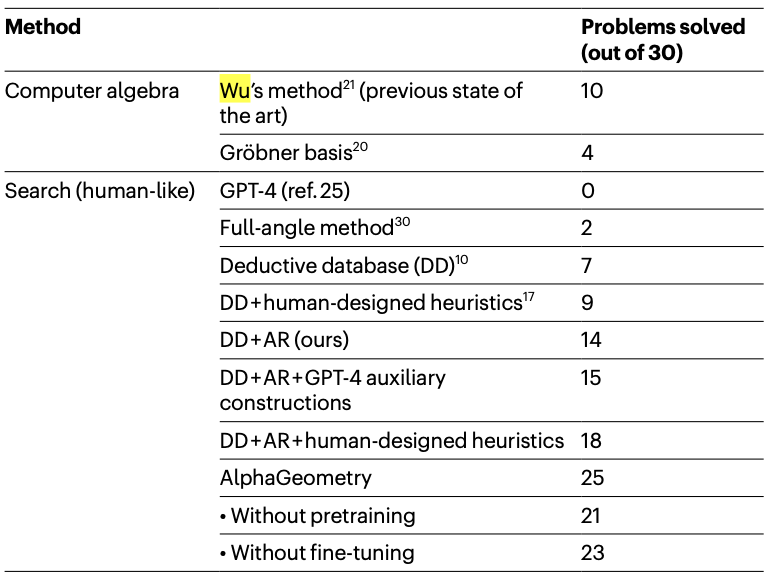

But still, the language model needs to be trained over some question-answer dataset. (You can see in the results table below that GPT-4 completely failed. Note that GPT-4 is built for general purposes, not for solving olympiad problems.) Instead of using the existing (actual) math contest problems, the authors use a synthetic dataset based on a symbolic engine. They especially randomly generate a lot of (nearly 1B) theorem premises - randomly drawn points, lines, and circles (but with sufficiently many intersections and special configurations like perpendicular lines or colinear points). Then, a symbolic engine produces new true statements based on the given premises. Such deduction steps form a directed acyclic graph, and for each note $N$ in a graph, one can trace back and find a minimal subgraph $G(N)$ of necessary premises and dependency deductions, i.e., a proof of $N$. This gives a datapoint $(\text{premises, conclusion, proof}) = (P, N, G(N))$. Note that the symbolic engine used combines deduction database (DD) and algebraic rules (AR).

For example, in the below figure, the green subgraph is the minimal subgraph of a deduction closure corresponding to the conclusion $HA \perp BC$. Note that the points $D$ and $E$ do not appear in the conclusion but in the proof, so they are regarded as auxiliary constructions. About 9% of the whole data contains such auxiliary constructions.

So DD + AR already gives a symbolic engine that works well (and is guaranteed to give true statements), but more is needed for Olympiad problems. Again, I emphasize that olympiad problems often need some clever auxiliary constructions, done previously using hand-crafted templates and domain-specific heuristics. In AlphaGeometry, this is done by language model - it is trained on the above synthetic data and learns to generate proofs through next-token prediction. More precisely, they are first (pre-)trained on the whole synthetic dataset, then fine-tuned on the ones with auxiliary constructions.

As a test, 30 Euclidean geometry IMO problems are chosen. You can see the result in the table below - it solved 25 problems among 30, which is slightly below the average 25.9 of IMO gold medalists. Note that DD + AR also got almost half correct. To get such a result, AlphaGeometry used <250 CPU workers with 4 V100 GPUs for a language model. They also sent the generated proofs to Evan Chen, a math coach and former Olympiad gold medalist, and he said:

“AlphaGeometry’s output is impressive because it is verifiable and clean. Past AI solutions to proof-based competition problems have sometimes been hit-or-miss (outputs are only correct sometimes and need human checks). AlphaGeometry does not have this weakness: its solutions have a machine-verifiable structure. Nevertheless, despite this, its output is still human-readable. One could have imagined a computer program that solved geometry problems by brute-force coordinate systems: think pages and pages of tedious algebra calculation. AlphaGeometry is not that. It uses classical geometry rules with angles and similar triangles as students do.”

They also mentioned that AlphaGeometry discovered some generalized statements of a problem by identifying unnecessary premises. For example, in the IMO 2004 P1, a condition on a point $O$ is unnecessary, and this slightly generalizes the problem.

You can find some examples comparing human-generated and machine-generated solutions in the Appendix. Note that we can use various techniques like complex numbers or barycentric coordinates, which are not available in AlphaGeometry.

So are we done? Will AI solve Millennium prize problems?

No, not yet. First, AlphaGeometry solves only Euclidean geometry problems, but not all the Olympiad problems. Hence, it is not intelligent enough to beat the current Olympiad kids who get gold medals in IMO - but I think the future is much closer than I initially thought (really, this paper changed my mind a lot). Especially, I believe that the challenge is achievable in 2 years.

Euclidean geometry is also a small part of the geometry that modern mathematicians study, which is a lot different. For example, here is a list of wide-open problems that do not belong to Euclidean geometry:

- (Lebesgue’s universal covering problem) What is the convex shape of the smallest area that can cover every planar set of diameter one?

- (Abundance conjecture) Every projective variety $X$ with Kawamata log terminal singularities over a field $k$ if the canonical bundle $K_X$ is nef, then $K_X$ is semi-ample.

- (Hopf conjecture) A compact, even-dimensional Riemannian manifold with positive sectional curvature has positive Euler characteristic. A compact, $2d$-dimensional Riemannian manifold with negative sectional curvature has Euler characteristic of sign $(-1)^d$.

- (Hodge conjecture) Let $X$ be a non-singular complex projective manifold. Then, every Hodge class on $X$ is a linear combination with rational coefficients of the cohomology classes of complex subvarieties of $X$.

The definition of geometry for mathematicians may be different from that for others. Anyway, these problems are the research problems that many people are interested in, and it may take at least ten years to solve at least one of these conjectures by AI. (FYI, Hodge conjecture is one of the six unsolved Millennium prize problems.)

Tags:math machine-learning