What should we do as mathematicians with AI?

In this post, I’m going to share some of my recent experiences using AI (which is an extremely vague word these days) in mathematics. Specifically, I’ll describe my experiences with two events on AI and mathematics - the FrontierMath symposium and the ML in Mathematics workshop - and introduce my recent work with Kyu-Hwan Lee on classifying Galois groups using ML.

FrontierMath Tier 4

I attended the FrontierMath Symposium, which was held in Berkeley about two months ago (huge thanks to Elliot Glazer and Epoch AI for organizing the event!). There were about 30-40 participants, of whom probably one or two were graduate students (including me). The goal of the symposium was to create a Tier 4 FrontierMath benchmark. A “Tier $\le$ 3” benchmark had already been created a few months earlier by several people, including some graduate students at Berkeley (I wasn’t one of them, as I misread Epoch AI’s email and forgot to submit my problem idea, even though I had several in mind).

From morning until evening, participants gathered at a secure location to discuss their own problems and refine them with feedback from others. Notably, an engineer from OpenAI generously provided us with a year’s access to ChatGPT Pro so that we could test our problems with the advanced models (I used o4-mini-high most of the time). We used them in temporary mode to ensure that OpenAI does not cheat on it.

While using these advanced models for the first time (since I didn’t want to pay $200 per month), I definitely learned a few things:

They are pretty good

These paid models are significantly better than the free versions of ChatGPT. One major difference is that Pro models can access the internet and search, whereas the free ones cannot. In other words, the knowledge of the free ChatGPT is limited to its training data, while Pro models can, in principle, access the most recent information by querying external sources. This explains why Pro models are already quite adept at literature searches and can “solve” some of the proposed problems by finding relevant papers.

They are not perfect

Obviously, many of the proposed problems remained unsolved. Although I don’t know much about all of the problems, most participants agreed that the models could not tackle problems requiring genuinely new ideas not yet present in the literature. For example, ChatGPT did not even know where to start with one of the Number Theory group’s problems and even congratulated the author of the problem (See this video to find the author of the problem.).

Are they thinking?

I think this is a philosophical question that isn’t well-defined, so there’s no definite answer. But if you ask me, I’d say:

-

No (80%), since they’re essentially generating sentences that “look like thinking”. The UI/UX of ChatGPT (and similar interfaces) is so well-designed that it makes people believe ChatGPT is actually thinking.

-

Yes (20%), because sometimes humans aren’t much different from these LLMs. When I was young, I liked to copy fancy formulas from popular math books - like Fermat’s Last Theorem by Simon Singh - even though I didn’t really understand them; I just enjoyed writing them. Maybe I was a poor, tiny language model back then. Also, most of(?) the recent reasoning models are using Chain of Thoughts prompting, by forcing it to “think” (again, this is not well-defined for me) step-by-step. Even if one argues that they are not thinking, the way they present the intermediate steps is quite useful.

More on FrontierMath

Check out Epoch AI’s website to learn more and see the current leaderboard. For now, officially, 4 out of 48 problems (except for the publicly available two sample Tier 4 problems) are solved by GPT-5. I was already surprised that models can solve more than zero problems of the benchmark.

Machine Learning and Mathematics at KIAS

While visiting Korea, I attended the ML and Mathematics workshop at KIAS. There were many great speakers working on ML-guided mathematics and formalizations (in Lean, mostly), and all the talk videos are available on the workshop website. My favorite talk was the first one by Geordie Williamson, which was about isosceles-free sets (from PatternBoost) and the Hirsch conjecture (from this paper)1. I’m pretty much convinced that ML can be used to find nice “examples” in mathematics from the lectures, and I plan to explore similar approaches (especially reinforcement learning) for my own problems.

I also met a lot of new (and old, not in the sense of their age) people during the workshop and discussed interesting research ideas. There were problems that I never considered, and they seem very promising ML-based investigations which are definitely worth trying.

Using ML in my own research (Learning Galois group of number fields)

After returning from the workshop, I finally finished the paper that I had been working on with Professor Kyu-Hwan Lee. A previous paper by He, Lee, and Oliver used logistic regression and decision tree models to classify Galois groups (and other invariants such as degree or class numbers), finding that the models could predict with high accuracy. Our paper explains why they work well, by interpreting the trained models.

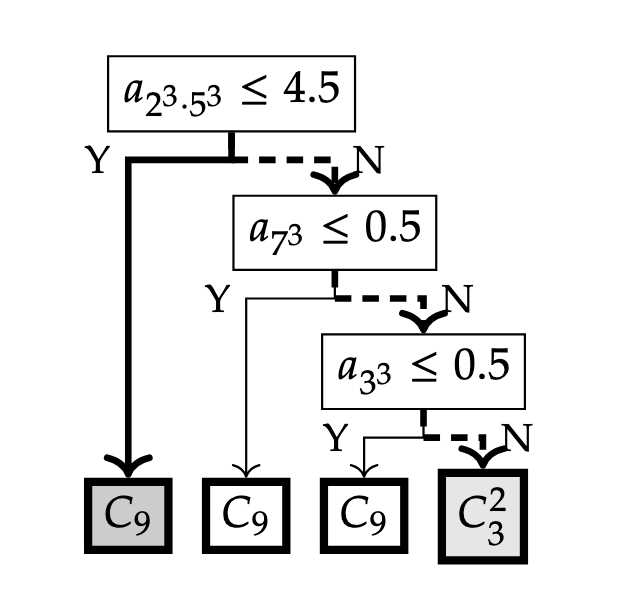

The most interesting case involved degree-9 extensions. If we restrict our attention to Galois extensions, there are two possible Galois groups: $\mathbb{Z}/9\mathbb{Z}$ or $(\mathbb{Z}/3\mathbb{Z})^2$. By using the first 1000 Dedekind zeta coefficients (for each $n \ge 1$, $a_n$ is the number of integral ideals $\mathfrak{a} \subseteq \mathcal{O}_K$ of index $n$), the decision tree model achieved 100%(!) accuracy on a test set2 for distinguishing between two groups. Especially, it is very easy to guess what the model is actually doing:

We found that the model only uses three coefficients out of 1000 - 1000, 343, and 27 - all of which are perfect cubes! More precisely, it predicts a Galois group to be $\mathbb{Z} / 9\mathbb{Z}$ if $a_{m^3} = 0$ for some $m \ge 1$. It turns out that this criterion holds for any degree 9 Galois extension, which was previously unknown (a similar result holds for any Galois extensions of degree $\ell^2$ for prime $\ell$). We also studied Galois extensions of degree 4, 6, 8, and 10, observing and proving additional interesting results by interpreting the ML models.

Use cases of ChatGPTs

There are at least two ways in which ChatGPT proved useful while writing the paper.

-

Literature search. It’s very good at locating papers and references. I asked for the statements of theorems that were likely known but that I hadn’t seen before, and it correctly provided the references. You definitely need the

Searchoption for this. -

Code generation. I needed LaTeX figures for the decision tree models and initially spent a lot of time drawing them one by one using the forest package. I realized I could ask ChatGPT to write Python code that generates the appropriate LaTeX code for the decision trees, which worked almost perfectly. Although I had to make a few follow-up requests to fix minor issues (such as escaping backslashes in the generated text), it handled them easily. You can view the chat history here with

o4-mini-high.

What should I (we?) do in the present and future as a mathematician

I hope my experiences have convinced you that AI can assist mathematical research in several ways: finding new (counter)examples, locating relevant papers, writing supplementary code, and more. As a concluding remark, I share my thoughts on how I plan to use AI in my future research.

-

Again, LLMs can serve as powerful, flexible search engines far beyond simple web searches. I will continue to use them to locate the papers I need so that I don’t waste time reproving known results. However, LLMs still suffer from hallucinations, which are nearly impossible to eliminate completely. Therefore, it’s crucial to carefully check any answers or cited references and verify the information before trusting it. That is definitely human’s work (at least for now, until we get formally verified LLM).

-

They can do “boring” things for you. You can ask the models to do not-fun part of your research, something you can definitely do yourself but you don’t want to do, so that you can focus on the fun part. Again, you need to check carefully if they give correct answers or bullshits.

For example, I had to do some tedious elementary computations with trigonometric series for my paper I just finished, such as computing the sum $\sum_{k=1}^{n} a^k \sin(k x)$. This can be done by using Euler’s formula and geometric series, but I may need to spend 5 minutes of my life. I can also try to google it to make sure that my computation is correct, which may need an additional 5 minutes of my life. Instead, I asked this to

o3-pro, and it gave me a formula. I’m pretty sure that this is recorded in a reference and probably it just copy-and-pasted the knowledge, but it can provide a reference and at least I can believe it. Althougho3-profailed a lot for more complicated computations,GPT-5 prosuccessfully did the same calculation with much fewer attempts (FYI, the paper will be on arXiv soon). -

One might ask an LLM to prove new theorems. This is clearly more difficult than searching for references, and LLMs struggle to produce proofs requiring genuinely novel ideas not present in the literature3. However, I found them useful even when they produced incorrect jargon, because they often pointed me toward the right references. Moreover, completely wrong ideas can sometimes inspire new insights; it’s common to get fresh ideas from discussions with mathematicians in other fields.

-

Not all AI tools are LLMs. There are many examples where (non-LLM) AI has helped mathematicians find new (extremal) examples or discover relations among mathematical objects previously unknown. For the former, reinforcement learning has shown success; for the latter, interpretability is key. Ideally, humans identify new patterns in the examples and relations generated by AI models, leading to the development of new theory.

-

It is clear that they are growing very fast. There are already 3-4 models claiming gold medals on this year’s IMO, and I also have some other examples that I have not mentioned in this post, where LLMs can actually solve easy but still nontrivial research problems completely. If this continues and eventually whatever AI solves a very hard open problem in mathematics, should we all quit math? My own answer is no. What I expect is that the AI will definitely contribute to solving some hard open problems, but it would be a collaboration between humans and AIs, not solely an AI’s work instead. I guess this is one possible future of AI in mathematics (which is already happening in some sense).

-

Since the advent of AlphaGo, Go players have begun studying the game based on AI’s moves. Of course, it has now become nearly impossible for humans to beat AI in Go, but I believe this situation has both advantages and disadvantages. AI is designed to make moves that maximize the probability of winning in Go, but it may no longer retain the artistic aspects that the game once had. (In fact, Lee Sedol retired from professional Go after his match with AlphaGo, and he mentioned in an interview that it was partly for such a reason.)

Similarly, if mathematical AI develops, it will ultimately be trained to return correct proofs as its highest goal — but in mathematics, producing a proof itself may not always be the only objective. Personally, I believe mathematical proofs can also be viewed as a form of art, and if AI is trained solely with the goal of finding the right answer, such “artistic” proofs may actually become harder to find. Just like how images generated by generative AI can sometimes evoke the uncanny valley, there is a good chance that proofs produced by a mathematical AI might not ultimately be the “Proofs from the Book” we truly desire. From this perspective, “human-scented proofs” will continue to be in demand.

-

There was one more problem about knot theory, which seems to be an in-progress work and not published yet. ↩

-

We also proved that there are infinitely many nonic Galois extensions that will be classified incorrectly under the tree above. But the discriminant of such fields is probably huge and does not appear in LMFDB. ↩

-

Again, this is not a well-defined claim, since it is hard to say what is a “new idea”. Almost all - probably all - ideas of mathematics are built upon the ideas from the past, so one can claim that all mathematics can be interpolated from the known results. However, some of the pioneering works are definitely based on “novel” ideas that have not appeared before. ↩

math machine-learning