ICML 2023 Review

I just returned from Honolulu, Hawaii, where this year’s ICML was held. Although I do not major in ML, I attended to present my work on homomorphic encryption-based transfer learning that was done while I was at CryptoLab. As a mathematician, most of the buzzwords were new to me, so I had to ask the authors or other friends for the definitions of the words I hadn’t seen before to understand what the papers were doing. Anyway, I met many of my old friends and some new people, and it was good to know what they were working on. There were over 7000 people at the conference, which was huge compared to any of the math conferences (maybe ICM or JMM have that many attendees). Understanding everything at the conference was impossible, so I needed choice and focus. I tried to attend all of my friends’ posters (with many stupid questions) and also visited the ones with interesting titles (especially math-ey ones). I’ll explain some of the interesting works that I’ve seen at the conference in my own words, which could be wrong. Let me know if there are any problems with my explanations. To read the papers, click the titles.

My favorite papers at ICML

HETAL: Efficient Privacy-preserving Transfer Learning with Homomorphic Encryption

This is our (CryptoLab) work that is accepted as an oral presentation. The paper’s primary goal is to show that HE-based Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning (PPML) is now practical, contrary to the common belief on the ineffectiveness of homomorphic encryption.

Homomorphic encryption is considered a holy grail of cryptography since one can perform computations over ciphertexts. This is well-suited for privacy-aware ML applications, especially when we deal with data that possess privacy concerns (e.g., medical images, financial records, …). Most of the HE schemes are lattice-based encryptions, whose hardness is equivalent to that of the lattice problems like the Shortest Vector Problem (SVP), which is widely believed to be unbreakable even with quantum computers. Especially, CKKS scheme supports SIMD approximate computations over real and complex numbers, which is a suitable choice for PPML applications. However, one of the major drawbacks of HE is that they are very slow, which prevents most people from using them in practice. Hence, it is essential to reduce the number of costly operations to boost the speeds of algorithms.

In our work HETAL (HE-based TrAnsfer Learning), we achieved practical performance (fine-tuning classifiers in an hour with a single A40 GPU) by optimizing computations in softmax approximations and encrypted matrix multiplications. For softmax, the existing approaches need to be better suited for the training purpose (they all used it for inference) since the domain of approximation is not enough to cover the range logits that increase as we train the models further. By combining the previous works on homomorphic domain extension and homomorphic comparison, we suggest a softmax approximation algorithm on a wide range with provable error bound that does not depend on the domain extension index. Note that it is essential to apply normalization (based on the comparison) to guarantee the error bound. Also, the bound is NOT optimal at all, and I have a vague idea to reduce the bound significantly, but I had not enough time to add it during the rebuttal phase.

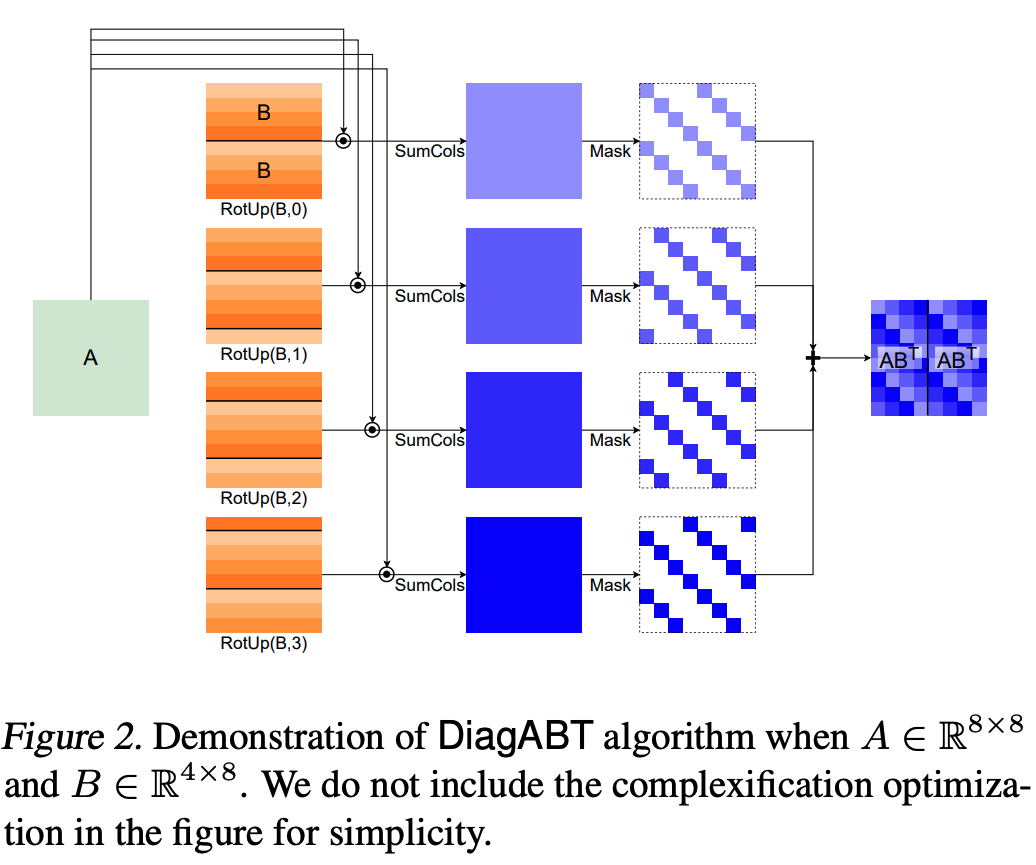

Another main component of HETAL is the encrypted matrix multiplication for computing logits and gradients. In a bird-eye view, four types of operations can be done on ciphertexts: SIMD addition, SIMD multiplication (Hadamard multiplication), SIMD complex conjugation, and rotation. One needs to implement matrix multiplication algorithms by using only these operations, so we need to consider (1) how to pack a given (possibly large) matrix as ciphertexts and (2) how to multiply these matrices only using addition, multiplication, complex conjugation, and rotation under the packing (in fact, you don’t need to understand any details of CKKS scheme to perform high-level optimizations for matrix multiplications). It is crucial to reduce the number of multiplications and rotations to reduce the computational complexity, which was our new algorithms’ main goal. Instead of applying previous encrypted matrix multiplication algorithms that compute $AB$ for given $A$ and $B$, we propose two separated algorithms ($\textsf{DiagABT}$ and $\textsf{DiagATB}$) that compute $AB^\intercal$ and $A^{\intercal}B$ respectively. Since a backpropagation requires transpose, which can be a costly operator for large matrices, using the separated algorithms that implicitly include transpose is much more efficient (in fact, there are no existing algorithms for homomorphic transpose for large matrices, although it is possible to suggest one). It is crucial to reduce the number of rotations (key switching), and this can be done by applying and developing techniques such as tiling, complexification, and partial rotation. Note that we have done only high-level optimizations by reducing the number of high-level operations (e.g., rotations). Some previous works have similar approaches (compute $AB^\intercal$ and $A^\intercal B$ separately), and our algorithms outperform these baselines by 1.8 to 320 times. The following figure describes $\mathsf{DiagABT}$ algorithm for $A \in \mathbb{R}^{8 \times 8}$ and $B \in \mathbb{R}^{4 \times 8}$ without complexification optimization. The intuition of the algorithm is to compute as many entries in the result matrix as possible, and they appear in off-diagonal manners as below.

I presented HETAL at several places, including KAIST and KIAS (thank you again for the invitations). Here is a list of questions that I’ve asked after these talks (including ICML):

-

How about fine-tuning multiple layers (small MLP) rather than a single layer (linear probing)? It is definitely possible to do this, but one needs to store the activations of each hidden layer for backpropagation. Also, the computational costs will increase depending on the number of layers. Also, the inherent error of the CKKS scheme could be non-negligible when fine-tuning MLP with many layers, so it may not be that trivial to generalize.

-

Further optimizations? I’m 200% sure that our algorithm is suboptimal, especially for the matrix multiplication algorithms. When writing the paper, the CryptoLab’s HEaaN library only supported single GPU acceleration, but now it can utilize multiple GPUs. The above matrix multiplication algorithms are well-suited for parallelization (we can compute each off-diagonal term separately and add them later), which may give further improvements. Also, as I mentioned above, no low-level optimizations are included in our matrix multiplication algorithms. Hence applying low-level optimization techniques (e.g., hoisting) may improve the speed of the algorithms. Also, recently developed techniques like HERMES (conversion between RLWE and LWE ciphertexts, accepted to Crypto 2023) would help to redesign fundamentally different algorithms.

-

Possible security issue of CKKS? There is a paper by Li and Micciancio on the security of CKKS. They observed that a decryption result in approximate homomorphic encryption leaks information about the LWE noise that can be used to recover the secret key. More precisely, they showed that the CKKS scheme is not $\mathsf{IND\text{-}CPA^D}$ secure, which is stronger than the standard $\mathsf{IND\text{-}CPA}$ security by further assuming that the decryption results are made publicly available. In HETAL, we consider the AutoML-like scenario. The clients (data owners) want to fine-tune models on their own private data, but they are assumed to have no expertise in ML. Hence they outsource the training to the server (with encrypted features), and clients will use the trained model for their own purpose. It may depend on the post-scenarios, but at least we have no $\mathsf{IND\text{-}CPA^D}$ security issue if clients keep the trained models private.

SpENCNN: Orchestrating Encoding and Sparsity for Fast Homomorphically Encrypted Neural Network Inference

There were only TWO papers on homomorphic encryption at ICML (among 1827 accepted papers), and this paper was a unique work on HE that was not ours. The paper is about the encrypted inference of CNN, which is one of the widely studied topics in HE-based PPML. The primary goal is to reduce the number of rotations, which is the most costly operation in CNN inference (other than bootstrapping). One of the most recent work on this topic is Lee et al., Low-Complexity Deep Convolutional Neural Networks on Fully Homomorphic Encryption Using Multiplexed Parallel Convolutions, which suggests Multiplexed Parallel Convolutions that compactly pack the multiple channel’s weight into single (or few) ciphertexts. (Another contribution of the paper is the imaginary-removing bootstrapping that handles catastrophic divergence of approximate RELU operations, but here I only concentrate on reducing computational costs of CNN layers.)

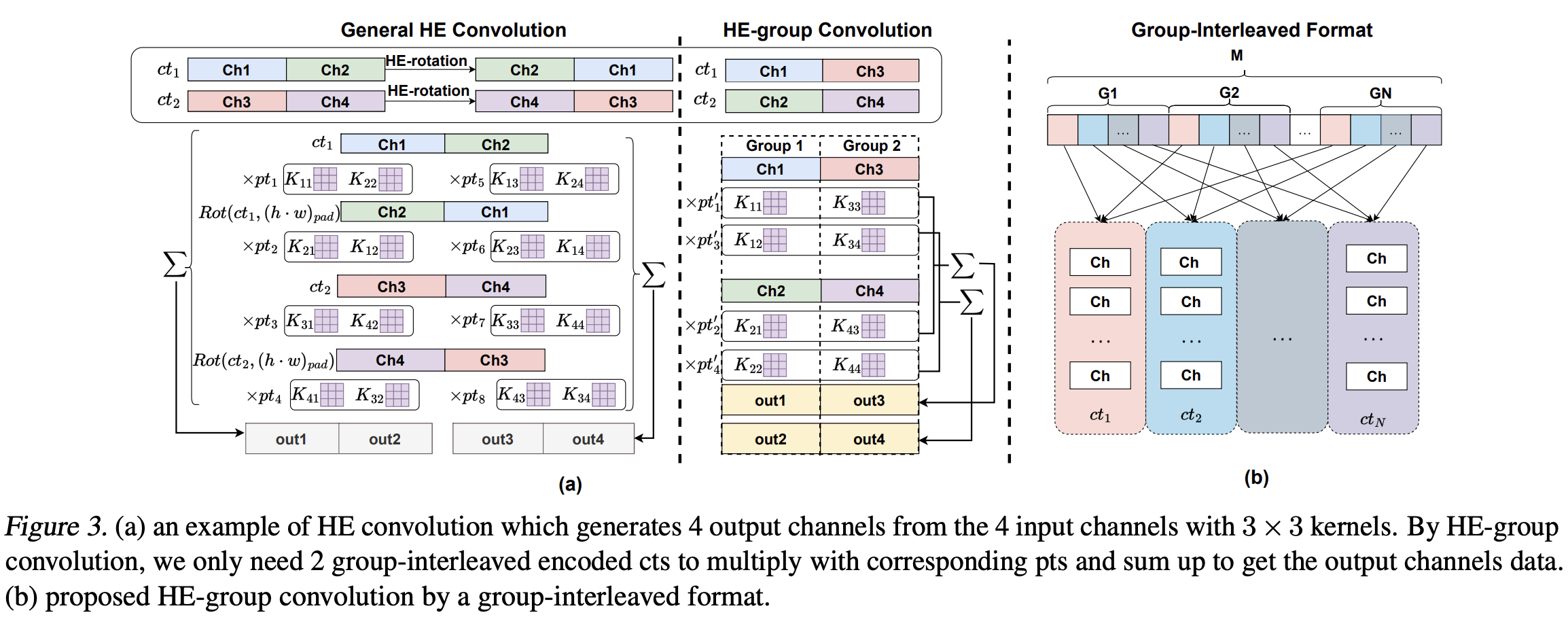

HE-based CNN inference consists of two types of rotations - inner rotations and outer rotations. Each input channel’s ciphertext needs to be rotated $K^2 - 1$ times (for the kernel size of $K$), and these rotations are called inner rotations. After the (inner-)rotated input channels are multiplied with (plaintext) weights, these will be summed up and result in an intermediate ciphertext for each input channel. These results are concatenated into a single ciphertext, and the outer rotations rotate the concatenated ciphertext, and output feature maps are obtained by summing up all the (outer-)rotated ciphertexts. Since each outer rotation introduces $K^2 - 1$ inner rotations, it is important to reduce the number of outer rotations.

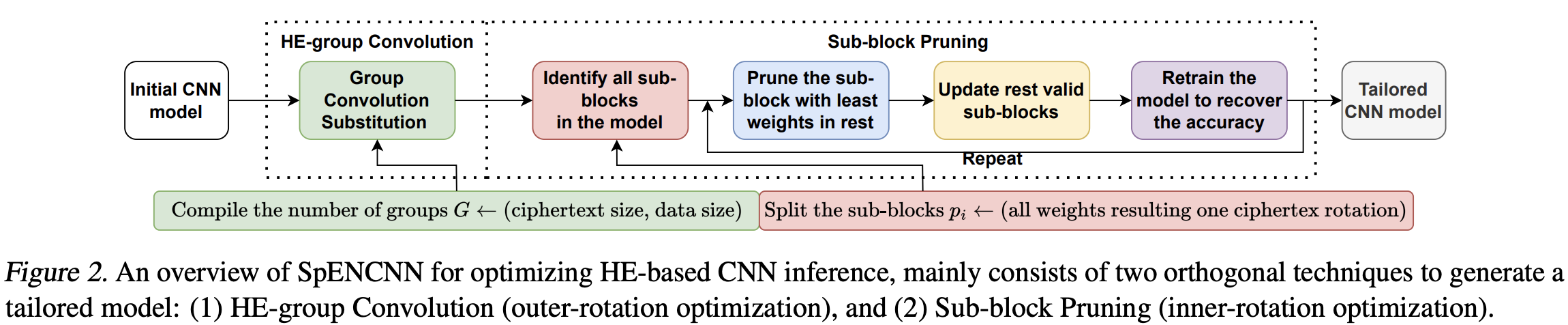

In this paper, they develop HE-group convolution and associated group-interleaved encoding to optimize channel locations on ciphertexts based on the number of convolutional groups and ciphertext size (Figure (a) below). To do this, we must replace the traditional row-major encoding with the group-interleaved encoding (Figure (b) below). This significantly reduces the number of outer rotations.

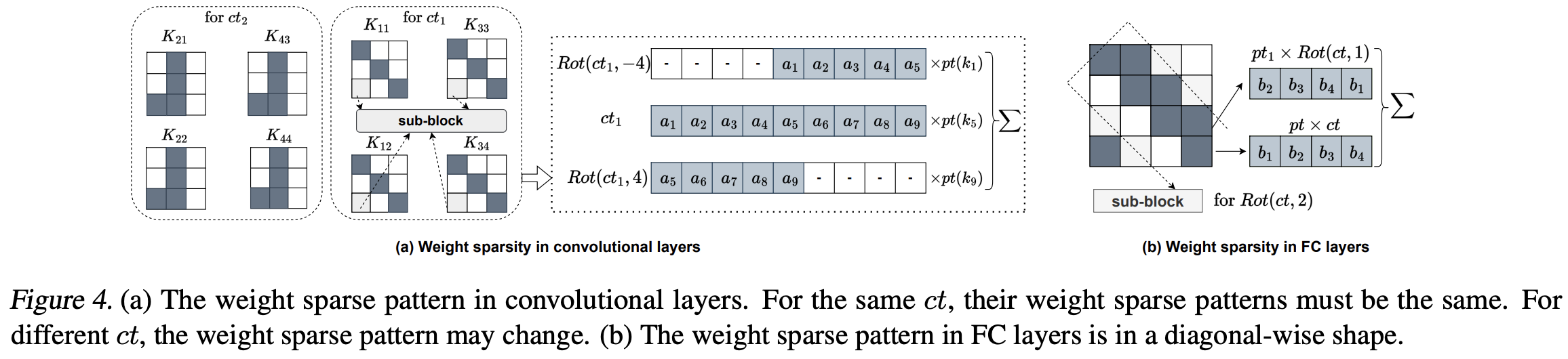

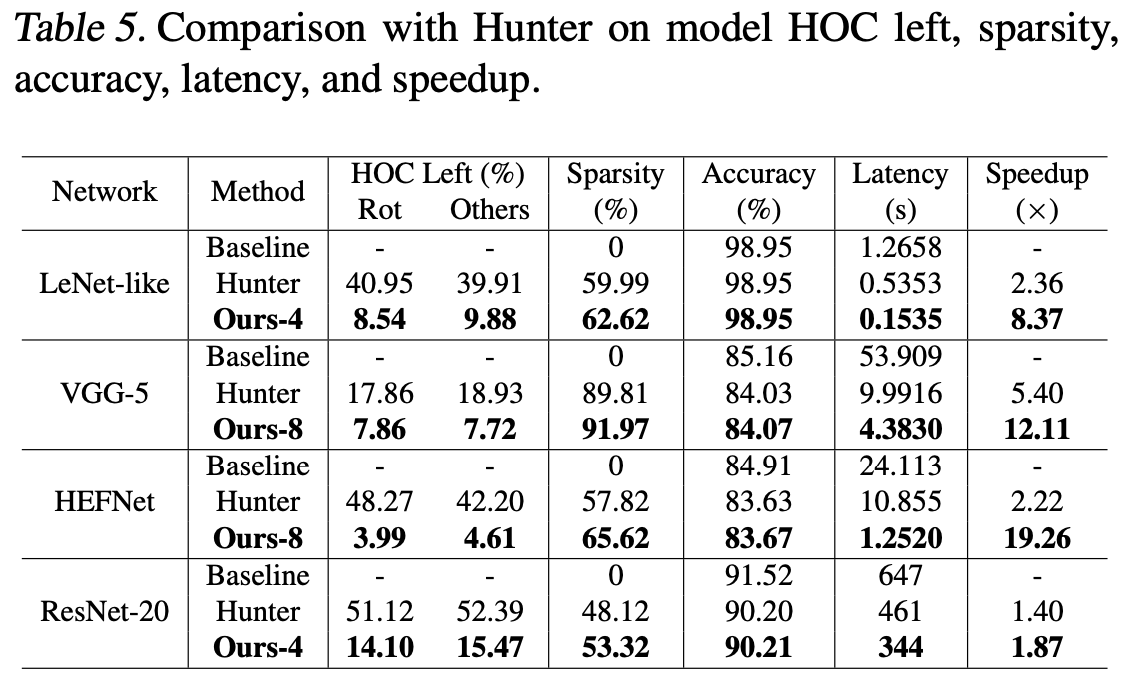

Another contribution of the paper is the Sub-block Pruning, which reduces the number of inner rotations by pruning weights that correspond to specific inner rotations. They defined the weight importance of the weight $w_{p_i}$ corresponds to a given sub-block $p_i$ as $||w_{p_i}|| / \dim (w_{p_i})$ (where the norm is $L^2$-norm) and did pruning-and-retraining based on the weight importance until one can recover the accuracy of the original (non-pruned) model. Note that the existing pruning methods (e.g. Han et al.) may not reduce the number of rotations at all; hence we need HE-packing-aware pruning methods as suggested to reduce computational costs. There’s a previous work called Hunter which has a similar approach to pruning, but SpENCNN was much more effective in terms of sparsity, accuracy, and latency (Table 5).

The following figure summarizes the overall process of SpENCNN. First, we find the optimal group number $G$ and use HE-group convolution with $G$ groups. Then we use sub-block pruning to reduce the number of inner rotations further. This results in a pruned CNN model with almost the same accuracy but with fewer inference costs.

Effectively Using Public Data in Privacy Preserving Machine Learning

This paper is about improving the existing differentially private SGD algorithm (DP-SGD) by leveraging public data. The original DP-SGD algorithm is done by clipping and adding (Gaussian) noise, which guarantees certain $(\varepsilon, \delta)$-differential privacy under the suitable choice of the variance of the noise. The authors found that clipping around an estimate of the gradient gives better utility than the naive clipping around the origin (which is called adaptive origin selection). This allows us to clip more aggressively (i.e., use smaller clipping values), and the algorithm (DP-SGDA) is described in Algorithm 1 of the paper. We need to estimate the gradients to clip the gradient near the adaptive origin, and they utilize public data for this purpose. The final algorithm is dubbed DOPE-SGD (which is dope). The authors also apply some advanced data augmentation methods (e.g., diffusion models) to improve performances further. In addition, using the ensemble of private models (majority voting or averaging) was also helpful.

Leveraging Proxy of Training Data for Test-Time Adaptation

This is a work done by one of my friends. The authors consider Test-Time Adaptation (TTA), the task of adapting a trained model to an arbitrary test domain using unlabeled input data on-the-fly during testing. TTA is helpful, especially when the distribution of the test data is largely different from that of the training data, which introduces generalization errors. One can only use the input of the test data but not the ground-truth labels. Also, it may be challenging to use the training data directly because of its possible presence of privacy issues.

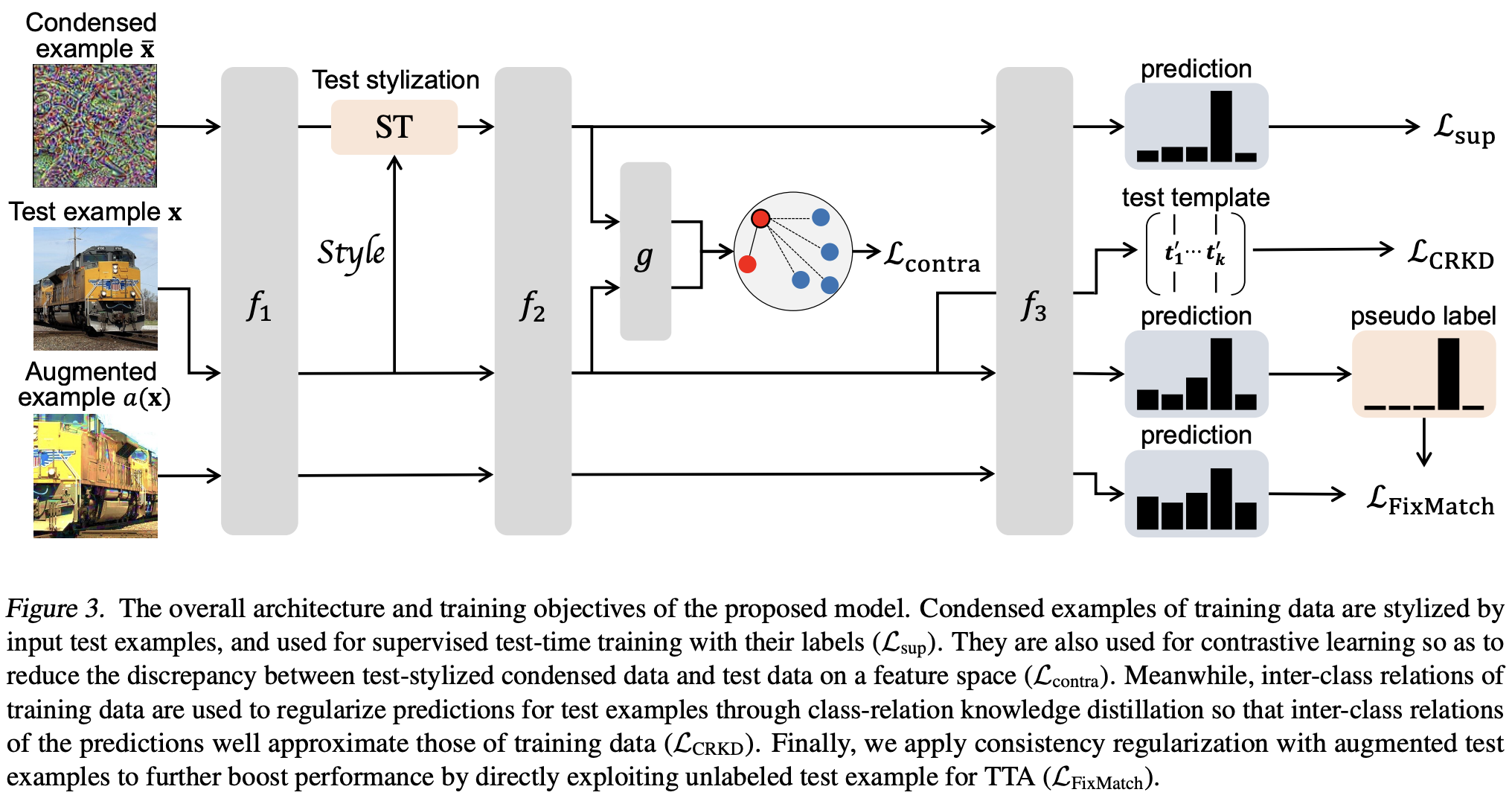

This paper utilizes two types of proxies for training data - style-normalized condensed data and class relations. Before TTA, they built a small set of synthetic condensed data representing each class with less private information. These are optimized by minimizing the empirical estimate of the maximum mean discrepancy between the style-normalized feature distribution (obtained from pre-trained models) of actual training data and the feature distribution of condensed ones for each class. These condensed data are included in the TTA via the supervised and contrastive losses.

Class relations are obtained from the weight matrix of the pre-trained classifier (each vector represents a class called class template). This can be thought of as an inter-class relation that usually remains consistent across different domains. During TTA, the class relations of training data are compared with that of test data via (CR)KD-loss with pseudo-labels. The test class templates are updated via exponential moving averages.

At last, they use FixMatch as a consistency regularization (also with pseudo labels). Hence there are four losses (supervised, contrastive, CRKD, and FixMatch), and the experiments show that their method outperforms the previous approaches on TTA.

Modality-Agnostic Variational Compression of Implicit Neural Representations

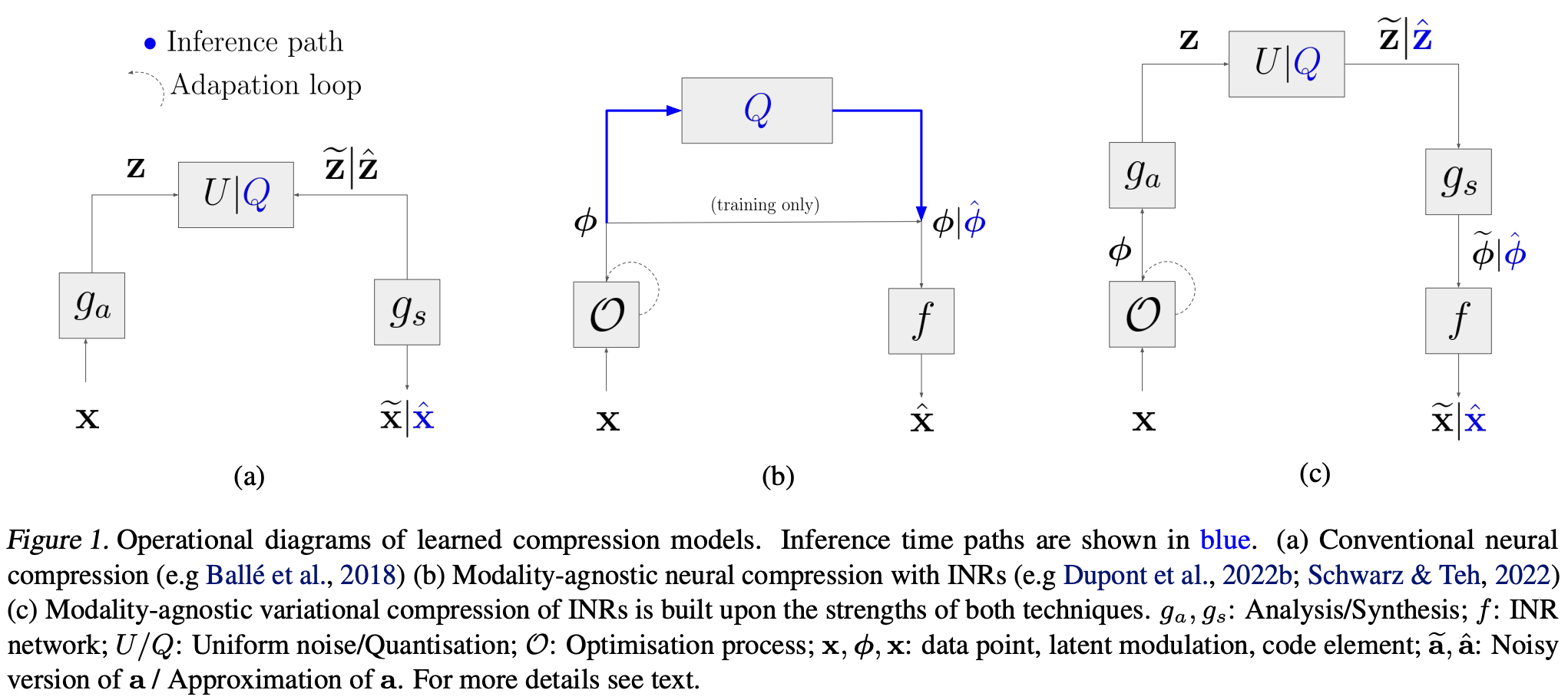

This is a work done by another one of my friends. Implicit Neural Representations (INR) considers each image/audio/point cloud as a (small) neural network that maps coordinates (e.g., pixels) to features (e.g., RGB values). One may use INR for compressing data, and this topic has been widely studied before. However, most of them are domain-specific, and this work considers modality-agnostic INR-based compression that does not depend on the domain of data.

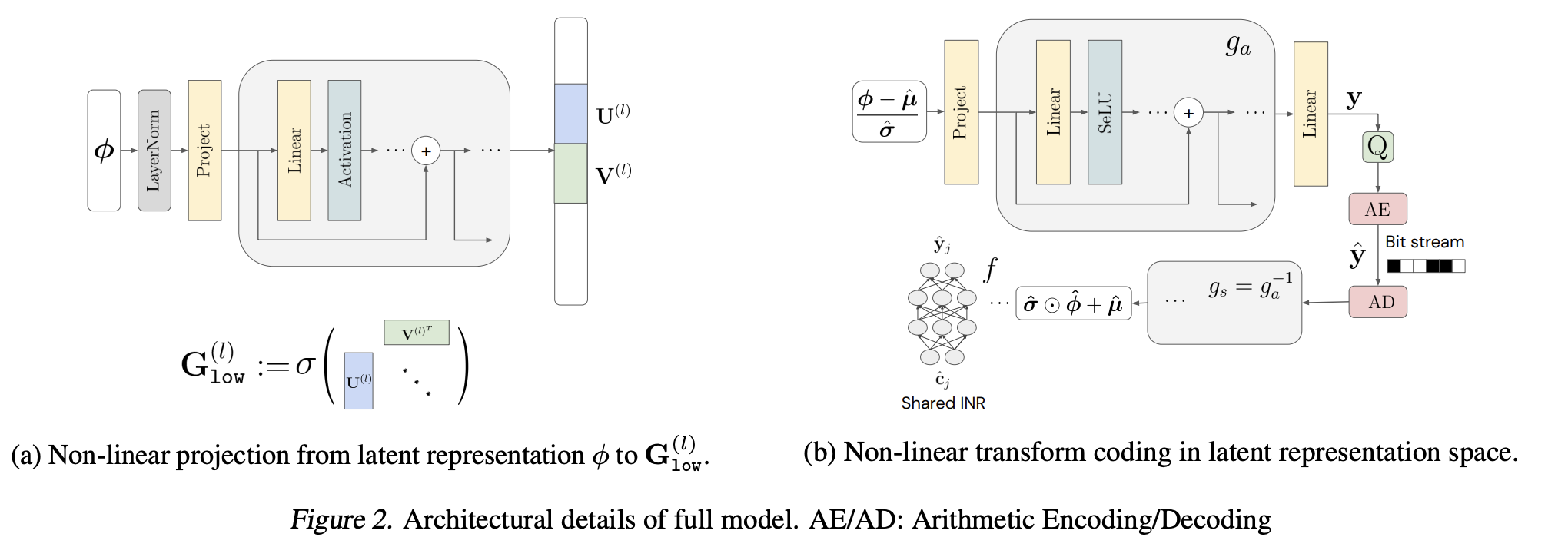

By combining the idea of INR-based compression and VAE-based compression (i.e., Neural compression), the authors propose VC-INR (Variational Compression of INR). Instead of using separated INRs $f^i$ for each data-item $\mathbf{x}^i$ (which may introduce high-dimensional parameter vectors with worse compression performances), they use shared INR $f(\cdot; \mathbf{\theta})$ with low-dimensional data-item specific parameters $\phi^i$ to obtain INRs $f(\cdot;\mathbf{\theta}, \phi^i)$ for each $\mathbf{x}^i$ (optimizing $\phi^i$ is done via Meta-Learning). Such $\phi^i$ are usually obtained by layer-specific modulations $\phi^i = [\mathbf{s}^{(1)}, \dots, \mathbf{s}^{(L)}]$ and applying these as shifts on each layer at the inference stage. Instead, they propose low-rank soft-gating with sinusoidal activation functions:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{c}^{(l - 1)} &\mapsto \sin(w_0(\mathbf{G}_{\mathsf{low}}^{(l)} \odot \mathbf{W}^{(l)} \mathbf{c}^{(l-1)} + \mathbf{b}^{(l - 1)})) \\ \mathbf{G}_{\mathsf{low}}^{(l)} &:= \sigma(\mathbf{U}^{(l)}\mathbf{V}^{(l)\intercal}). \end{align*}\]The central hypothesis is that $\mathbf{G}_{\mathsf{low}}^{(l)}$ acts as a subnetwork selection method. Also, adding LayerNorm and residual connection stabilizes the training of such low-rank parametrizations.

The modality-agnostic property comes from the VAE component of VC-INR, where $g_a$ (and $g_s$) serve as modality-agnostic data-item transformations. These are trained to minimize the compression loss, which is the sum of the code’s rate and the signal’s distortion.

It was quite interesting that VC-INR is much better than the classical compression methods, such as JPEG, MP3, and AVC/HEVC (in terms of PCNR).

A Watermark for Large Language Models

This paper is already reviewed in the previous post. Note that the paper is one of the outstanding paper award recipients of this year’s ICML.

Cross-Entropy Loss Functions: Theoretical Analysis and Applications

For training multi-class classification models, the standard choice of the loss function is the Cross-Entropy Loss. But why? I always wonder about this but haven’t found any satisfactory answer before. In this paper, they present a theoretical analysis of a broad family of loss functions, comp-sum losses, that has a form of

\[\ell^{\mathrm{comp}}_{\Phi_1[\Phi_2]}(h, x, y) = \Phi_1\left(\sum_{y' \neq y} \Phi_2(h(x, y) - h(x, y'))\right)\]where $\Phi_2$ is a non-decreasing function upper bounding $\mathbf{1}_{u \geq 0}$ for $u \in \mathbb{R}$ and $\Phi_1$ is a non-decreasing auxiliary function. Especially, they consider $\Phi_2(u) = \exp(-u)$ and

\[\Phi_1(u) = \Phi^\tau(u) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{1 - \tau}((1 + u)^{1-\tau} - 1) & \tau \ge 0, \tau \neq 1 \\ \log(1 + u) & \tau = 1 \end{cases}\]for $\tau \geq 0$. This family of losses includes sum-exponential loss ($\tau = 0$), Cross-Entropy loss (or multinomial logistic loss, $\tau = 1$), generalized cross-entropy loss ($1 < \tau < 2$), and MAE loss ($\tau = 2$).

In this paper, the authors proved the following $\mathcal{H}$-consistency bound for this family of losses, which is also proven to be tight.

Theorem Assume the hypothesis set $\mathcal{H}$ is symmetric and complete. Then, for any $\tau \in [0, \infty)$ and any $h \in \mathcal{H}$, the following inequality holds:

\[\mathcal{R}_{\ell_{0-1}}(h) - \mathcal{R}_{\ell_{0-1}}^*(\mathcal{H}) \\ \leq \Gamma_\tau(\mathcal{R}_{\ell_{\tau}^{\mathrm{comp}}}(h) - \mathcal{R}^{*}_{\ell_{\tau}^{\mathrm{comp}}}(\mathcal{H}) + \mathcal{M}_{\ell_\tau^{\mathrm{comp}}}(\mathcal{H})) - \mathcal{M}_{\ell_{0-1}}(\mathcal{H})\]where $\Gamma_\tau: [0, \infty) \to [0, \infty)$ is a certain family of functions with explicit formula satisfying

\[\Gamma_\tau(t) \leq \begin{cases} \sqrt{2^\tau(2-\tau)t} & \tau \in [0, 1) \\ \sqrt{2n^{\tau - 1}t} & \tau \in [1, 2) \\ (\tau - 1)n^{\tau - 1} t & \tau \in (2, \infty) \end{cases}.\]

Here $\mathcal{R}_\ell(h)$ (resp. $\mathcal{R}_{\ell}^{\ast}(\mathcal{H})$) is the generalization error (resp. the best in-class expected loss), and $\mathcal{M}_\ell(\mathcal{H})$ is the minimizability gap, defined as

\[\mathcal{M}_\ell(\mathcal{H}) = \mathcal{R}_\ell^\ast(\mathcal{H}) - \mathbb{E}_x [\inf_{h \in \mathcal{H}} \mathbb{E}_y [\ell(h, X, y) | X = x]]\]which is always non-negative. When the minimizability gap vanishes (e.g. when $\mathcal{H} = \mathcal{H}_\mathrm{all}$ is the set of all measurable functions), then $\tau > 2$ is more favorable than $\tau \leq 2$ since the error is bounded by $O(\epsilon)$ with $\epsilon = \mathcal{R}_{\ell_\tau^{\mathrm{comp}}}(h) - \mathcal{R}^{\ast}_{\ell_\tau^{\mathrm{comp}}}(\mathcal{H})$ for $\tau > 2$, while we only have $O(\sqrt{\epsilon})$ bound for $\tau \in [0, 2]$. However, the minimizability gap is nonzero in general, and one needs to analyze it further. This is given in Section 4 of the paper, and they proved that (certain upper bound of) the minimizability gap is non-increasing with respect to $\tau$.

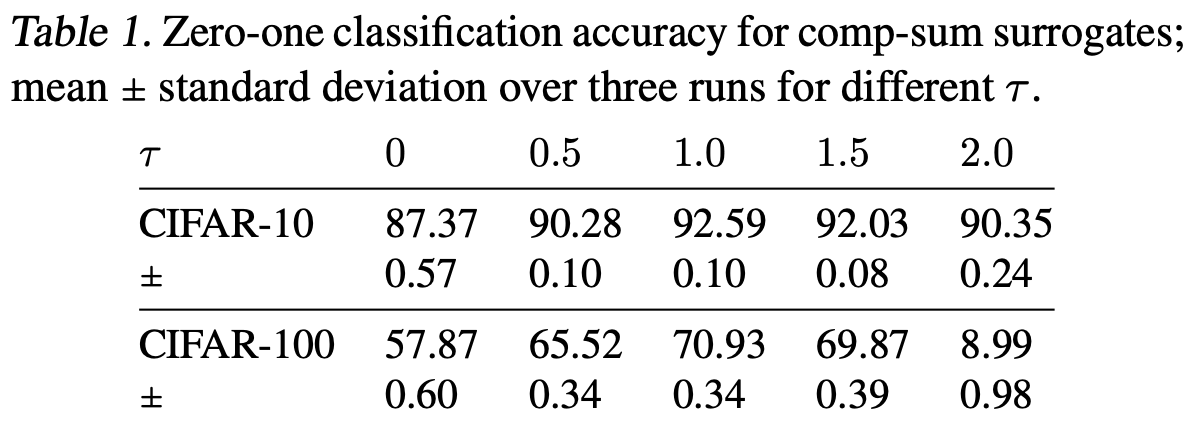

In their experiments, they trained ResNet-34 with the comp-sum losses for $\tau \in \{0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0\}$ with CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The below table shows that $\tau = 1$ outperforms $\tau = 0$ or $\tau = 0.5$, which is consistent with the above analysis since all three losses have the same square-root functional form and the magnitude of the minimizability gap decreases with $\tau$. For $\tau \geq 1$, the performances with $\tau = 1.0$ and $\tau = 1.5$ are similar, and they outperforms the MAE loss ($\tau = 2$). The authors explain this phenomena with the dependence of the multiplicative constants in $n$ that increases in $\tau$.

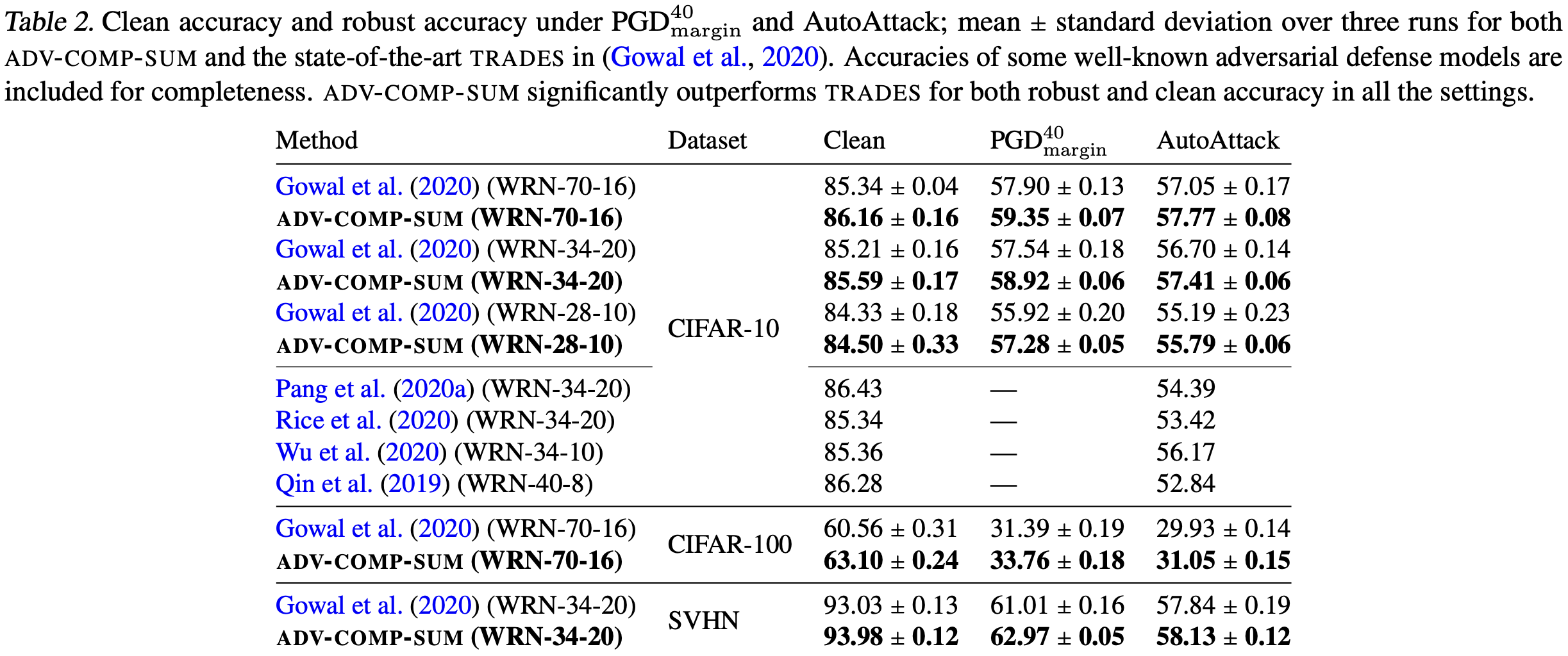

They also considered adversarial setup and proved similar bound for smooth adversarial comp-sum losses (Theorem 5.2 and Corollary 5.3). In their experiments, they showed that minimizing such losses (ADV-COMP-SUM algorithm) outperforms existing adversarial training algorithm like TRADES.

Biases in Evaluation of Molecular Optimization Methods and Bias Reduction Strategies

This paper is about evaluation methodology for molecular optimization. The main goal of optimizing molecules is to maximize certain property function $f^\ast$, but we may not know the function itself or find it costly to evaluate it. Instead, people often train a proxy predictor (plug-in performance estimator) $\hat{f}$ on a dataset $\{(m_i, f^{\ast}(m_i))\}_i$ and use it as an evaluator. In this work, the authors find that such an evaluator is biased in two ways: misspecification bias and reuse-and-finiteness bias. The first bias comes from the deviation between the proxy evaluator $\hat{f}$ and the true estimator $f^\ast$, where the second bias comes from the finiteness of the dataset and using it for both training generator and estimating performance metrics. Note that the second error is bounded as $O(1/N)$ where $N$ is the number of training data, which simply decreases as $N$ increases.

They also propose methods to reduce the biases. The misspecification bias comes from the covariance shift, and applying covariance shift adaptation while learning the predictor reduces the bias. In addition, conditioning the generator to generate molecules similar to those in the dataset also helps to reduce the misspecification bias. The reuse-and-finiteness bias can be reduced by using the bootstrapping methods.

In fact, the method can also be applied to domains other than molecular generations, especially when the ground-truth scorer is unavailable. I asked the presenter, and he agreed, although I don’t have any examples in other domains with similar situations.

Scaling Vision Transformers to 22 Billion Parameters

This paper was somewhat famous even before it was accepted (it already has over 60 citations and 42 authors from Google). Since there’s an official blog post on it by Google, I’d not replicate it here. The key ingredients are parallel Attention-MLP blocks and Asynchronous parallel linear operations.

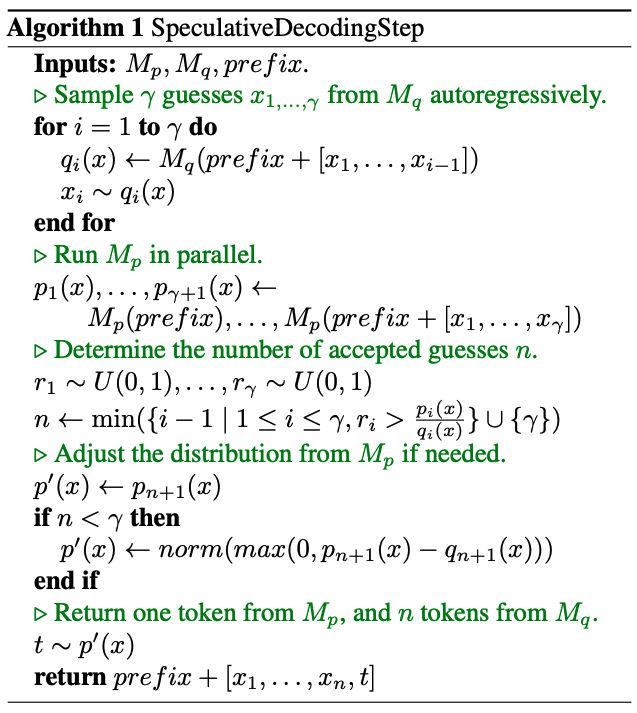

Fast Inference from Transformers via Speculative Decoding

Most of the LLM requires autoregressive decoding at the inference stage (one token at once), which is the performance bottleneck. In this paper, the authors introduce speculative decoding, which does not change the output distributions but can compute several tokens in parallel. The main idea is to utilize smaller LMs first (which may have enough performances for easy subtasks) and modify some of the outputs (in parallel) by comparing the output distributions of small models with those of the original (larger) models. It is easy to show that we obtain the same output distribution by rejecting the token $x$ with probability $1 - \frac{p(x)}{q(x)}$ when $q(x) > p(x)$ (and keeping it if $q(x) \leq p(x)$). They also provide an analysis of the reduction factor (the expected number of tokens produced by a single run of the algorithm) by considering both wall time and the number of arithmetic operations to choose the optimal number $\gamma$ of tokens to be generated by small LMs and compare these with experimental values.

List of other interesting papers that I can’t review since I’m lazy

Here is a list of papers that looks interesting, but I cannot review them since I have yet to read them thoroughly, and I’m too lazy to read them. I may write separate posts once I read them and find them attractive.

- Diffusion Probabilistic Models Generalize when They Fail to Memorize

- Learning-Rate-Free Learning by D-Adaptation

- SparseProp: Efficient Sparse Backpropagation for Faster Training of Neural Networks at the Edge

- Resurrecting Recurrent Neural Networks for Long Sequences

- Architecture-Agnostic Masked Image Modeling – From ViT back to CNN

- Convex Geometry of ReLU-Layers, Injectivity on the Ball and Local Reconstruction

- Hyperbolic Representation Learning: Revisiting and Advancing

- Differentially Private Sharpness-Aware Training

- Differential Privacy has Bounded Impact on Fairness in Classification

- Differentially Private Optimization on Large Model at Small Cost

Other events at ICML (and Honolulu)

There were many events at ICML, especially social events. Since I’m neither ML nor a social person, I didn’t attend many of the events, but I’ve been to two of them - ML in Korea and Jane Street lunch. Obviously, ML in Korea is for Korean ML researchers, hosted by Naver and sponsored by other AI startups. There were over 200 people and very crowded. The seats were divided into groups based on their research interests like NLP, Diffusion models, Vision, etc. Sadly, there was no privacy section, so I sat on some random seat next to my coauthor. The hosts gave some quizzes with prizes, and the first quizzes were doing human MLM with paper titles, i.e., fill the blanks in the title of the given paper presented at this year’s ICML. I know some papers (Scaling ViT to 22B and DetectGPT), but most of them are the ones I had never seen before. OX quizzes were much harder, but my random number generator worked pretty well. Eventually, I got the following prize at the event (this is a masking tape with some character that represents a tired graduate student).

For the Jane Street lunch, I got an invitation email about it, and honestly, I had no idea why they invited me (they may know my email since I applied to their fellowship last year, and also, they figured out that I’d participate in ICML, but how?) Anyway, I met some Jane Street people there, and it was pretty fun (and the food was also nice). But honestly, the conversation with a random non-Jane Street person who is working at IBM Tokyo and had an experience with HE was much more interesting. I also attended his poster session on molecule stuff (which is introduced above).

But, the most important point of this year’s ICML is that it was held in Hawaii (which also explains why there were so many attendees). Although I’m not an outgoing person, I did turtle snorkeling and also visited some beaches near the conference center and the hotel. I also visited HoMA, Honolulu Museum of Arts, which exhibits a wide range of arts in various regions, including Honolulu, Egypt, Indonesia, Japan, China, and Korea. The museum was quite big, and it took almost 2 hours to visit all the places.

I didn’t attend the tutorials and workshops since I did not know about the topics. Also, I misunderstood that the tutorials were doing some live coding by following instructions, but they were just another type of workshop, eventually explaining the organizer’s work on the subject. But now I regret it a bit since I could attend these events and learn some ongoing ML trends.

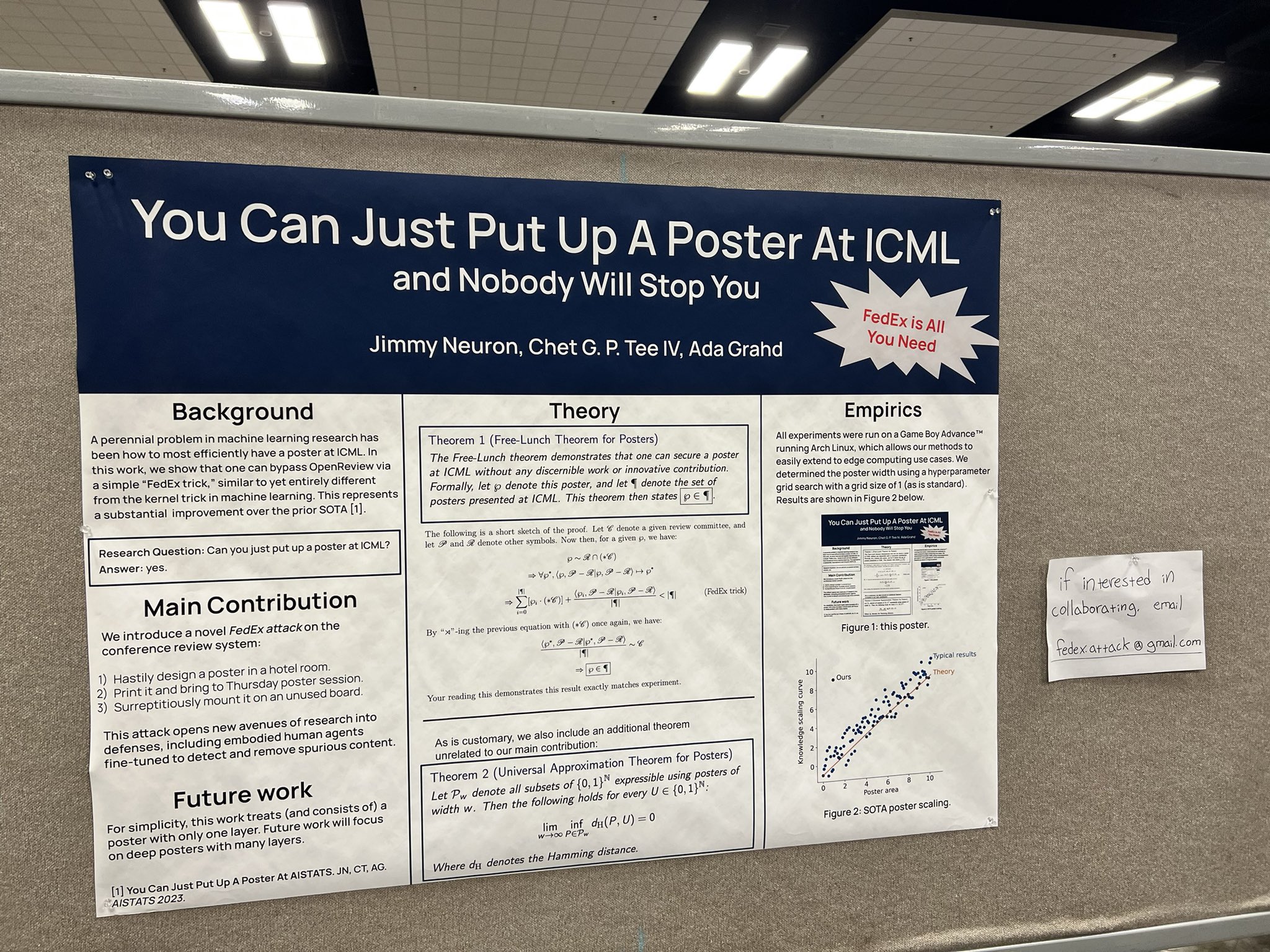

I may end this post with my favorite poster at ICML:

machine-learning