Algebraic proof of modular form inequalities for optimal sphere packings

I uploaded a new paper on arXiv about modular form inequalities appear in the proof of optimality of $E_{8}$ and Leech lattice sphere packings by Viazovska and Cohn-Kumar-Miller-Radchenko-Viazovska. The paper can be summarized as:

We have “algebraic” proofs of the inequalities that do not require any numerical analysis.

Story

The history of the problem itself can be found in the introduction/preliminary of my paper or the first few slides of this. Instead, I will share my own history and thought process on this project.

I learned about the problem when Viazovska announced the proof, and give a presentation on it when I was a senior undergraduate student. Of course, I didn’t fully understand the proof, but I knew that the proof uses modular forms and one need to prove some inequalities between modular forms, where the original proofs use approximations based on bounds of Fourier coefficients and numerical analysis (interval arithmetic). Then I forgot about the problem for a while, until 2023 Fall when Dan Romik introduced his new proof of Viazovska’s inequalities in $8$ dimension at UC Berkeley RTG seminar. After the talk, I asked him the most obvious question one can ask: what about $d = 24$? He said that it would be a good project for graduate students, and I decided to work on it as a “side project”, since I already had a problem that I was working on.

After reading the CKMRV paper carefully, I found that the first “easy” inequality I have to prove is already not easy. One has to prove that the following modular form is positive on the (positive) imaginary axis:

\[F = 49 E_2^2 E_4^3 - 25 E_2^2 E_6^2 - 48 E_2 E_4^2 E_6 - 25 E_4^4 + 49 E_4 E_6^2.\]I tried to express $F$ as a sum of squares, but failed (and now I believe it is not possible - at least only using level $1$ forms). Then I stuck. Luckily, I found that someone implemented quasimodular forms in Sage, so I decided to play with it. Then I found $F$ have positive Fourier coefficients upto $q^{10000}$, and conjectured that this is true for all coefficients (which directly implies positivity of $t \mapsto F(it)$). Of coures, this is a stronger than what I need to prove, and I didn’t know how to prove it.

After that, I did some literature search and learned what quasimodular forms are. In my opinion, the correct way to think them are modular forms with differentiations. In a computational viewpoint, differentiations of level 1 quasimodular forms can be computed using Ramanujan’s formula

\[E_{2}' = \frac{E_{2}^{2} - E_{4}}{12}, \quad E_{4}' = \frac{E_{2}E_{4} - E_{6}}{3}, \quad E_{6}' = \frac{E_{2}E_{6} - E_{4}^{2}}{2}\]and product rule. I differentiate $F$ using Sage, and I got the following:

\[\begin{align*} F' = \frac{7}{6}(&49 E_{2}^{3} E_{4}^{3} - 25 E_{2}^{3} E_{6}^{3} - 72 E_{2}^{2} E_{4}^{2} E_{6} \\ &- 15 E_{2} E_{4}^{2} + 81 E_{2} E_{4} E_{6}^{2} - 10 E_{4}^{3} E_{6} - 14 E_{6}^{3}) \end{align*}\](simply call F.derivative()). As you can see, differentiating quasimodular form increases weight by 2 and depth by 1. The original $F$ has weight $16$ and depth $2$, so $F’$ has weight $18$ and depth $3$. However, I found that multiplying $F$ by a multiple of $E_{2}$ and subtract from $F’$ cancels out $E_{2}^{3}$ terms, and moreover, the result factors into a product of two forms:

Surprisingly, each factor are essentially derivatives of $E_{4}$ and $-E_{10} = - E_{4} E_{6}$, hence they should have positive Fourier coefficients. After I observe this, I wonder if this would imply positivity of $F$. It turned out to be true, and the idea is to solve the differential equation, or equivalently, observe the monotonicity of $t \mapsto F(it) / \Delta(it)^{7/6}$. I also found that the cancellation phenomena is quite general, and the operator $D - \frac{7}{6} E_{2}$ actually has a name - Serre derivative of weight $14$. This proved the “easy” inequality.

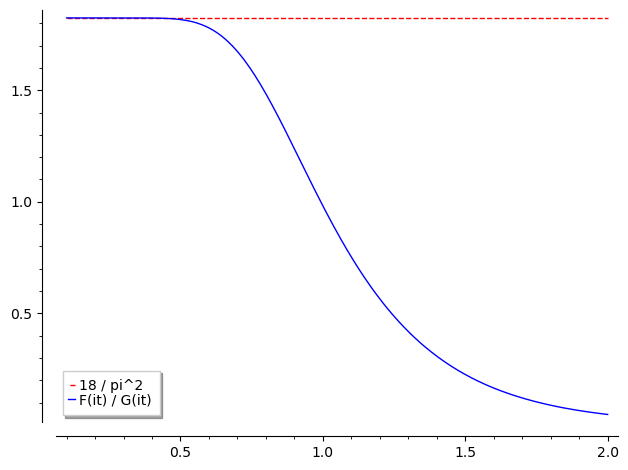

For a while again, I had no progress on the “hard” inequality. Of course, I tried to mimic Romik’s proof, but his proof is quite delicate and it was not clear for me how to mimic it in $d = 24$ case. Especially, we need to prove that $F$ has nonnegative Fourier coefficients, which does not follow from the previous argument (using Serre derivative). Hence I decided to understand $d = 8$ case more carefully, especially trying myself to re-prove the (hard) inequality. After playing with Sage for few more weeks, I observed the monotonicity of quotient (Figure 1), and how nicely its derivative factors, which yield the Proof 1.

Luckily, the same strategy seems to work for 24-dimensional case (2nd inequality), but proving the positivity of $F’G - FG’$ seems much harder than the 8-dimensional case. The biggest difference is that it does not factors as nicely as the 8-dimensional case - it factors as

\[F'G - FG' = H_{2}^{5} (H_2 + H_4)^{2} H_{4}^{2} \cdot K\]where $K$ is a weight 14, depth 2, level 2 quasimodular form (it does not factor as a product of depth 1 quasimodular forms). But one interesting observation was that the actual level $K$ was $\Gamma_{0}(2)$, not $\Gamma(2)$.

Then the next question is - how to cook up positive quasimodular forms of level $1$ or $\Gamma_{0}(2)$. I tried a lot of things, but what actually worked is using extermal quasimodular forms and old forms arise from them. Especially, it is possible to express $K$ as a positive linear combination of

\[\begin{align*} H_{2}(z) X_{12, 2}(2z), &\quad H_{2}(z) (X_{12, 2}(z) - 2^{10} X_{12, 2}(2z)), \\ (H_{2}(z) + 2 H_{4}(z)) X_{10, 2}(2z), &\quad (H_{2}(z) + 2H_{4}(z)) (X_{10, 2}(z) - 2^{8} X_{10, 2}(2z)) \\ H_{2}^{2}(z) X_{8, 2}(2z), &\quad H_{2}^{2}(z) (X_{8, 2}(z) - 2^{6} X_{8, 2}(2z)) \end{align*}\]where all the forms above are positive (in fact, completely positive). There are two comments on this:

- This proof is not contained in the final version of the above paper, since I found a much simpler proof that saves almost 5~6 pages. But it has its own interest and may appear in a future paper (hopefully…).

- When I found this, I thought that I finished the project. Unfortunately, I realized there’s a third inequality for 24-dimensional case, which does not appear in 8-dimensional case.

For the issue in 2, I had to decide whether 1) upload the incomplete version on the arXiv, or 2) spend more time on the third inequality. At first, I thought that there’s no algebraic proof of the inequality, because it include exponential and polynomial terms (not purely modular). However, after playing with Sage again, I found that there might be a workaround that may leads to an algebraic proof. The current proof in the paper is quite different from the initial approach (which didn’t work well), but anyway there it is and that’s the end.

Why it matters

So I proved statements that are already known to be true. Then why it matters at all? Maybe, it does not matter at all. But I can try to promote the result as follows:

- Algebraic method is more well-suited than numerical method to prove some results that are uniform in infinitely many dimensions (maybe I’m wrong), since numerical methods cannot be applied easily to prove infinitely many statements (inequalities). In fact, my original goal was to prove a uniform bound (of course, I don’t have a proof yet). Unfortunately, the conjectural LP bound is weaker than the current best known upper bound.

- Better for formalization. At least in Lean, it is more inclined toward “algebra” than “analysis”, so this proof of the inequalities might be more easily formalizable than other analytic proofs. UPDATE: Check out the ongoing project on formalizing sphere packing in dimension 8: here

Why computer matters

What I learned from the project is that Sage or any math programs are extremely helpful. Since I’m not Ramanujan, I cannot plot the graphs of quotients $F(it) / G(it)$ or even factor $\partial_{14}F$ with hands, but Sage can do this in milli seconds. Maybe I’m too much biased toward computer-assisted mathematics, but I strongly believe that computer will be used a lot in future math research (much more than now).

Tags:math